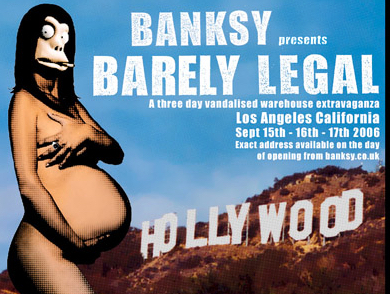

Barely Legal was the third major exhibition after the Turf War and Crude Oils. It took place on the weekend of 16 September 2006 in a warehouse in Los Angeles and was billed as a “three-day vandalised warehouse extravaganza”.

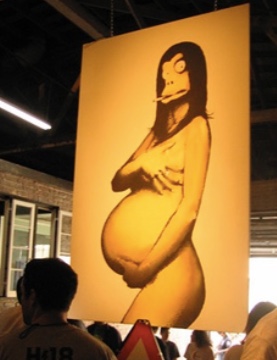

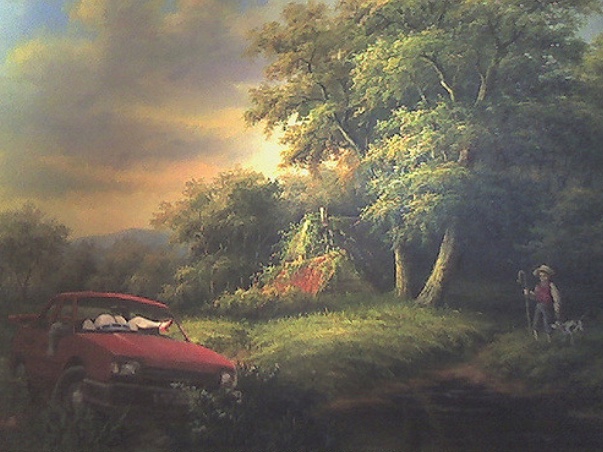

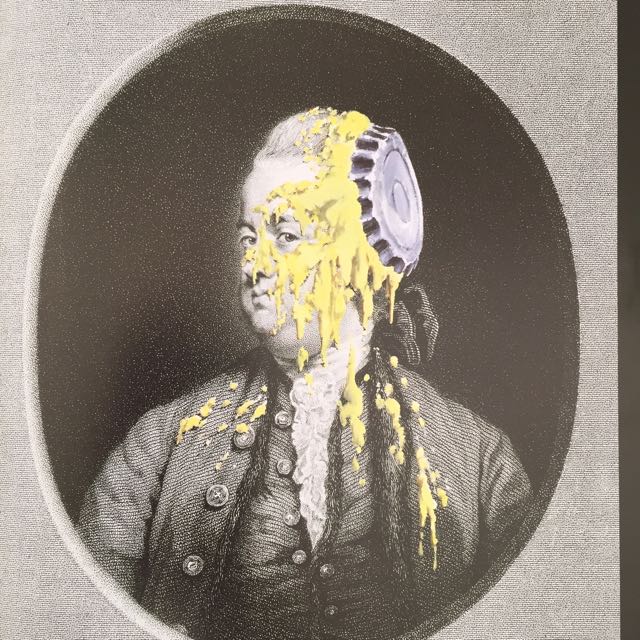

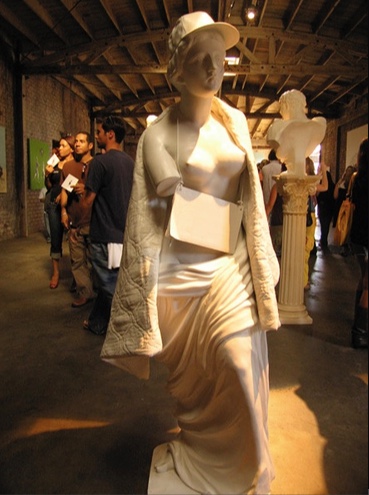

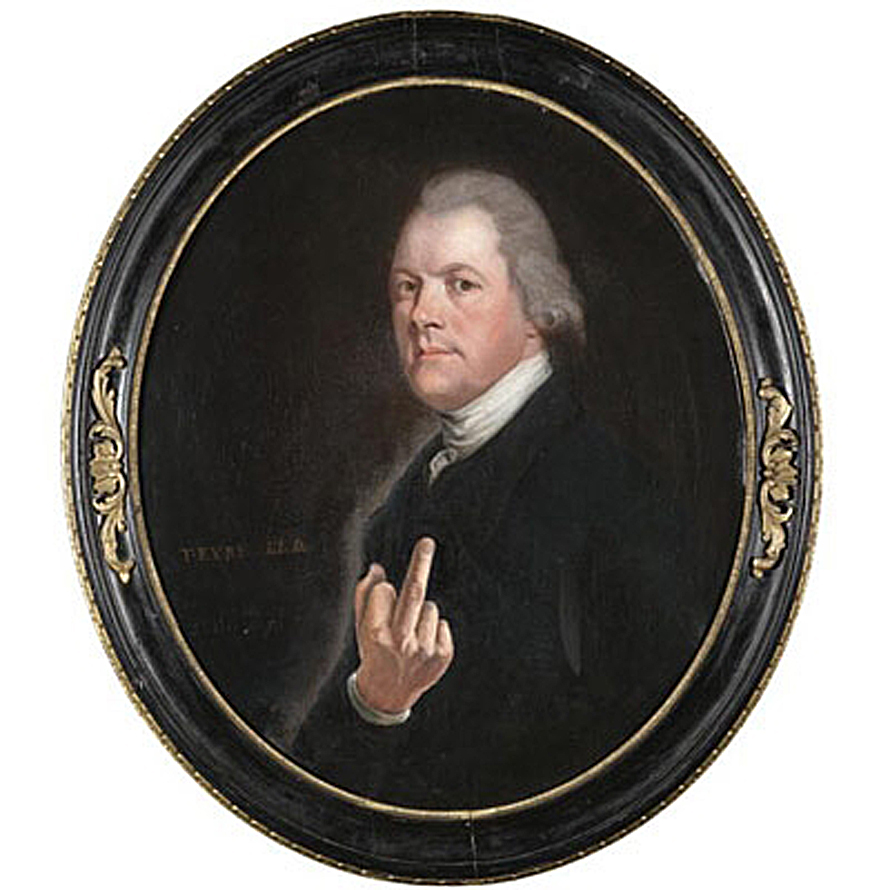

The exhibition featured a live “elephant in the room,” painted in a pink and gold floral wallpaper pattern. According to leaflets handed out at the show, “the elephant in the room” is intended to draw attention to the issue of world poverty. Banksy continued exploring the modified oil genre from the previous Crude Oils exhibition.

–

The New York times published a review of the show on 6 September 2006:

In the Land of Beautiful People, an Artist Without a Face

By Edward Wyatt

LOS ANGELES, Sept. 15 — As a metaphor for problems that people are uncomfortable talking about, “the elephant in the room” is not the most original.

But then, few people actually put the elephant in the room, paint it red and adorn it with gold fleurs-de-lis to match the brocade wallpaper, and then dare viewers not to talk about it.

Banksy, perhaps Britain’s most notorious graffiti artist and public prankster, has done just that with “Barely Legal,” a new show at an industrial warehouse in Los Angeles, as part of what his spokesman says is his first large-scale exhibition in the United States. Such a show — complete with advance publicity, an opening party with valet parking and Hollywood glitterati, including Jude Law and his posse, and sales of numbered prints at $500 each — would seem to go against Banksy’s rebel image.

“Yes, there probably is some contradiction,” Banksy’s spokesman, Simon Munnery, said on Thursday in an interview at the warehouse in a commercial district east of downtown. (Details on the exhibition site can be found at http://www.banksy.co.uk.)

“It depends on what he does with the money, right?” Mr. Munnery added. “Maybe he makes more art. Maybe he’s getting more ambitious.”

Banksy makes a habit of not revealing himself in public, a practice that is part survival technique and part publicity ploy, but he has shown projects in the United States. Most notoriously, he carried his own artworks into four New York institutions last year — the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum and the American Museum of Natural History — and hung them on the gallery walls, next to other paintings and exhibits, without guards’ taking notice. He has performed similar stunts at museums in Britain.

Earlier this month Banksy surreptitiously placed a blow-up doll dressed as a Guantánamo detainee inside the fence of the Big Thunder Mountain Railroad ride at Disneyland, where it apparently remained for more than an hour before park officials shut down the ride and removed it. Recently he also smuggled 500 altered versions of Paris Hilton’s new CD into record stores around Britain and placed them in the racks.

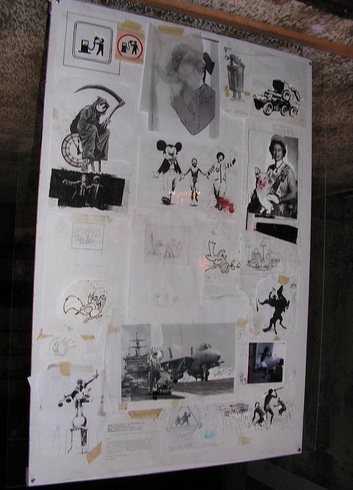

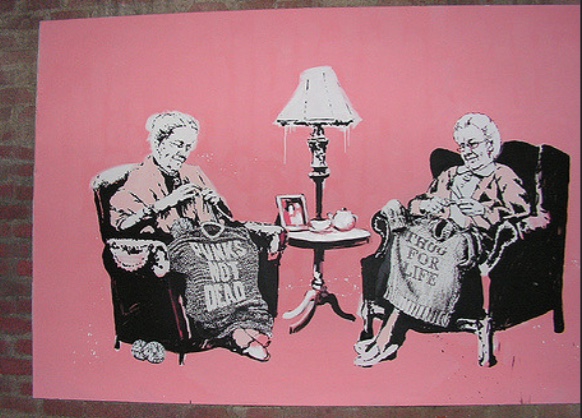

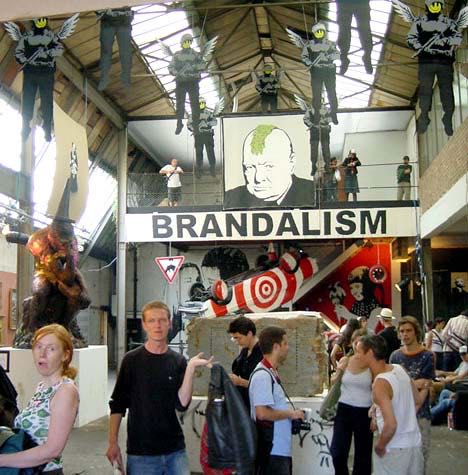

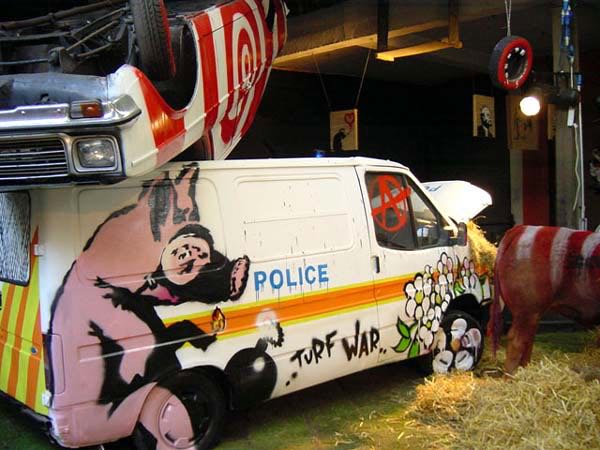

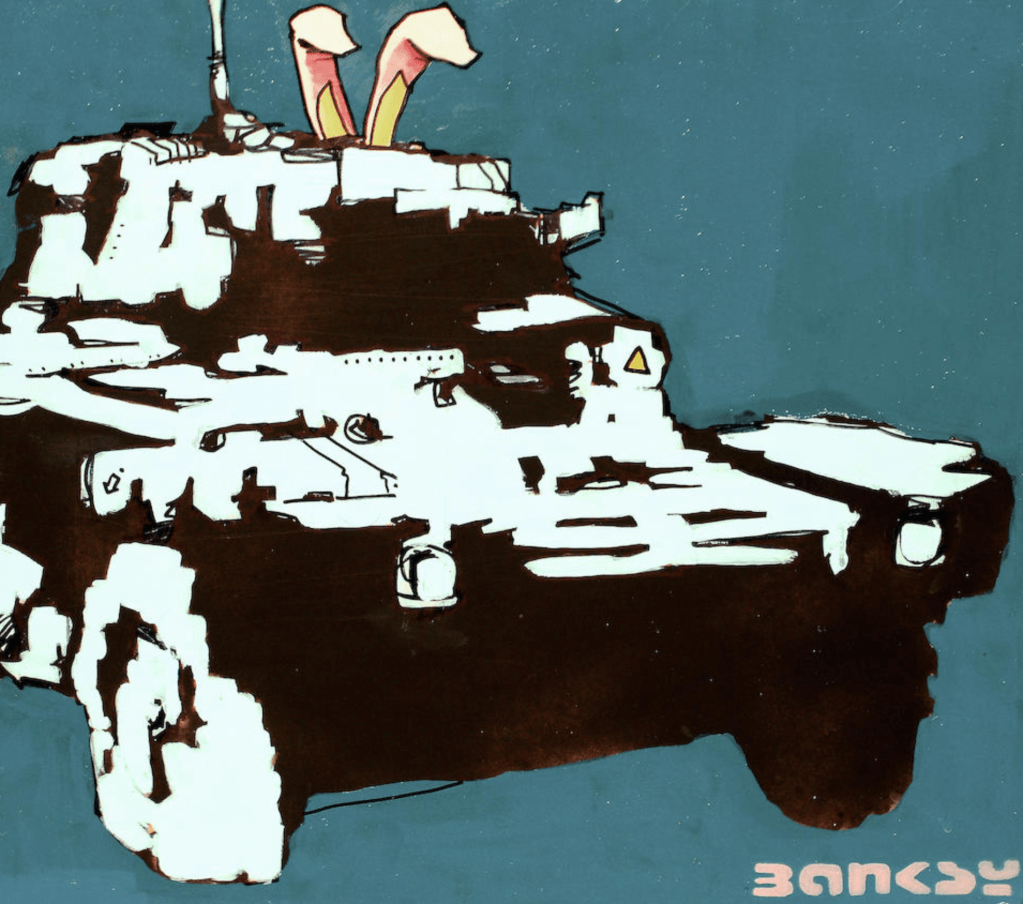

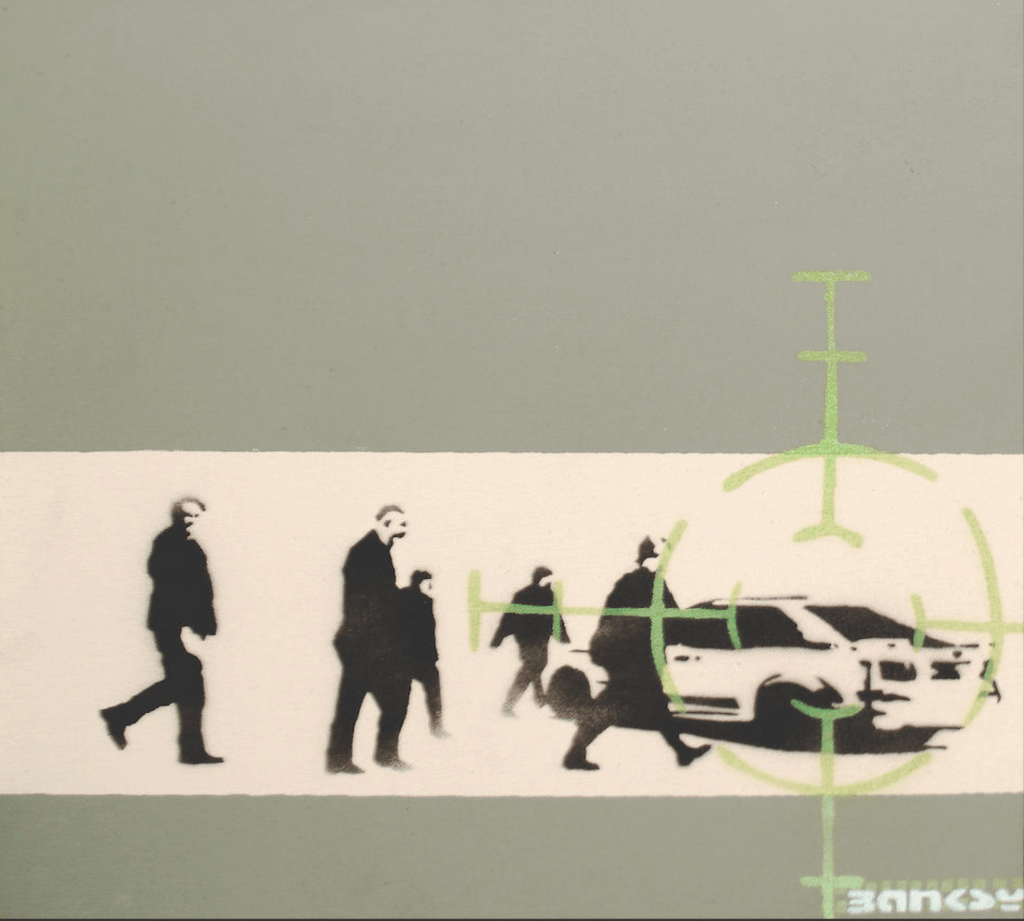

All of those stunts are featured in a video that loops continuously at the show, which also includes two large rooms displaying stenciled images on canvas, sculptures and mixed-media productions, like the panel van with the notice on the back, “How’s My Bombing?” and an 800 number that links to a Navy recruiting office in Phoenix.

All of this is arranged around a sort of mock-self-loathing, elephant-in-the-room theme, or, as Banksy puts it in a handout: “1.7 billion people have no access to clean drinking water. 20 billion people live below the poverty line. Every day hundreds of people are made to feel physically sick by morons at art shows telling them how bad the world is but never actually doing something about it. Anybody want a free glass of wine?”

Many of the pieces have been seen before, either on the streets of London and other cities, in books of Banksy’s work or at his Web site. Many comment on war, like the stark image of a television camera crew filming a child amid ruins as the producer holds back aid workers to allow for just one more shot.

With seemingly so much to say, and being so clearly desirous of an audience, surely Banksy would show up at his first big exhibition in the United States, then?

Perhaps he’s the gaunt chap over there, with the nose ring and the “Tagger Scum” T-shirt, touching up the gold fleurs-de-lis on the elephant. Or is he Mr. Munnery, who is also a British comedian with a penchant for rhetorical questions (“Why are some people dying of obesity, and others are starving to death?”) and who, in fact, looks quite a bit like the mysterious hatted and bearded fellow who appears in Banksy’s videos?

“I’m not him,” said Mr. Munnery, who is credited for “additional inspiration and assistance” in one of Banksy’s books, titled “Cut it Out,” which was distributed to journalists as part of the promotion for the new show.

The Guardian, the British newspaper, has identified Banksy as Robert Banks, an artist from Bristol. Some commentators have identified him as Stephen Lazarides, a photographer who set up Banksy’s Web site and whose gallery is the sales agent for the Banksy prints at the show here.

Mr. Munnery would not divulge the artist’s identity. Banksy “requests the right to remain silent,” he said. “He insists on it.”

But the artworks are Banksy’s alone, he said. “And I do know that some of them took literally hours to paint.”

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/16/arts/design/16bank.html