Four stencils appeared on 13 December in The Jungle, a Calais refugee camp. Since Dismaland, it’s clear that Banksy’s preferred theme is the refugee situation in Europe.

some sort of Banksy retrospective

Four stencils appeared on 13 December in The Jungle, a Calais refugee camp. Since Dismaland, it’s clear that Banksy’s preferred theme is the refugee situation in Europe.

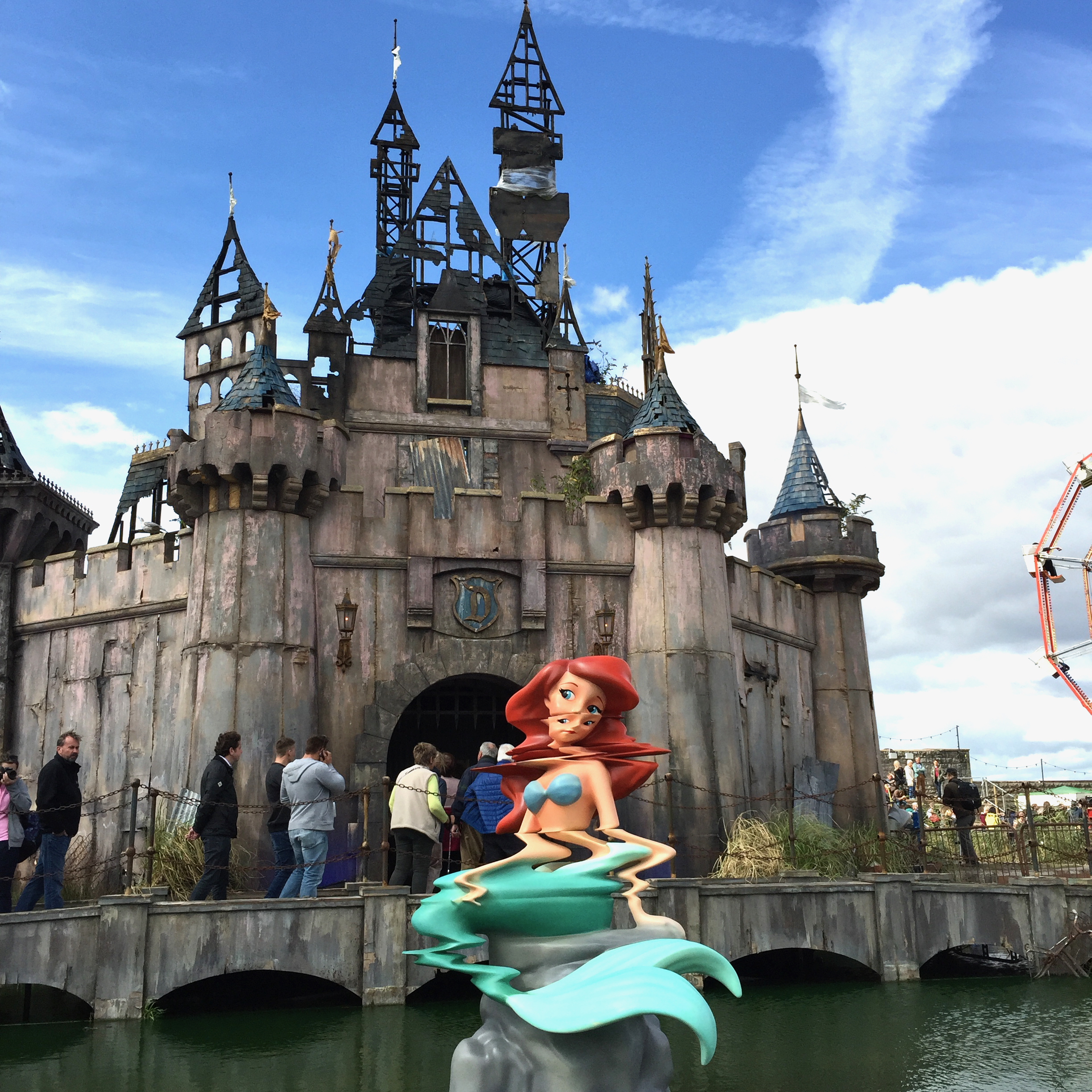

Dismaland was pop-up art exhibition, financed and organised by Banksy, staged in the seaside town of Weston-super-Mare, 30 km south of Bristol. Opening on August 21, 2015, and closing on September 27, 2015, this “bemusement park” was a dark, satirical twist on traditional theme parks like Disneyland, billed by Banksy as a “family theme park unsuitable for children.” Housed in the abandoned Tropicana lido, it combined dystopian aesthetics with sharp social commentary, targeting themes such as consumerism, celebrity culture, immigration, and law enforcement.

The project was shrouded in secrecy during its development. It featured approximately 15 original works by Banksy alongside contributions from 58 other artists, including notable names like Damien Hirst, Jenny Holzer, and Jimmy Cauty. One can say that Dismaland in itself was a big art installation, in which all the visitors played a part. Attractions included a dilapidated castle, a crashed Cinderella carriage surrounded by paparazzi (evoking Princess Diana’s death), and a grim reaper on a bumper car, all underscored by a deliberately bleak atmosphere. The park also offered twisted versions of classic fairground attractions—think a carousel with a butcher carving a horse or impossible games like “topple the anvil with a ping pong ball.”

Dismaland had one key element, the contradiction: the sad bemusement park, rude stewards, and a helpdesk closed 24/7 to the public and the Hawaiian music at full volume was played in “minor” and at varying speeds, interrupted every ten minutes by strange messages from child voices. Everything at Dismaland was the other way around.

Dismaland drew 150,000 visitors over its 36-day run, with 4,000 tickets available daily at £3 each. The intentionally rude staff, mock security checks, and a gift shop exit added to the experience’s irony. Its impact extended beyond art, boosting Weston-super-Mare’s economy by an estimated £20 million. After closing, some materials were repurposed for refugee shelters, and Banksy’s coin-operated “Dream Boat” was later donated to the charity.

Critics were divided—some praised its bold absurdity, while others dismissed it as heavy-handed or gimmicky. Regardless, Dismaland remains a standout in Banksy’s career, blending his signature provocation with an immersive, chaotic spectacle.

The show featured 58 artists from the 60 Banksy initially invited to participate. The list included Damien Hirst, Jenny Holzer, Jimmy Cauty, Tracy Emin, Jeff Gillette, David Shrigley, Paco Pomet, Escif, Peter Kennard, and many more.

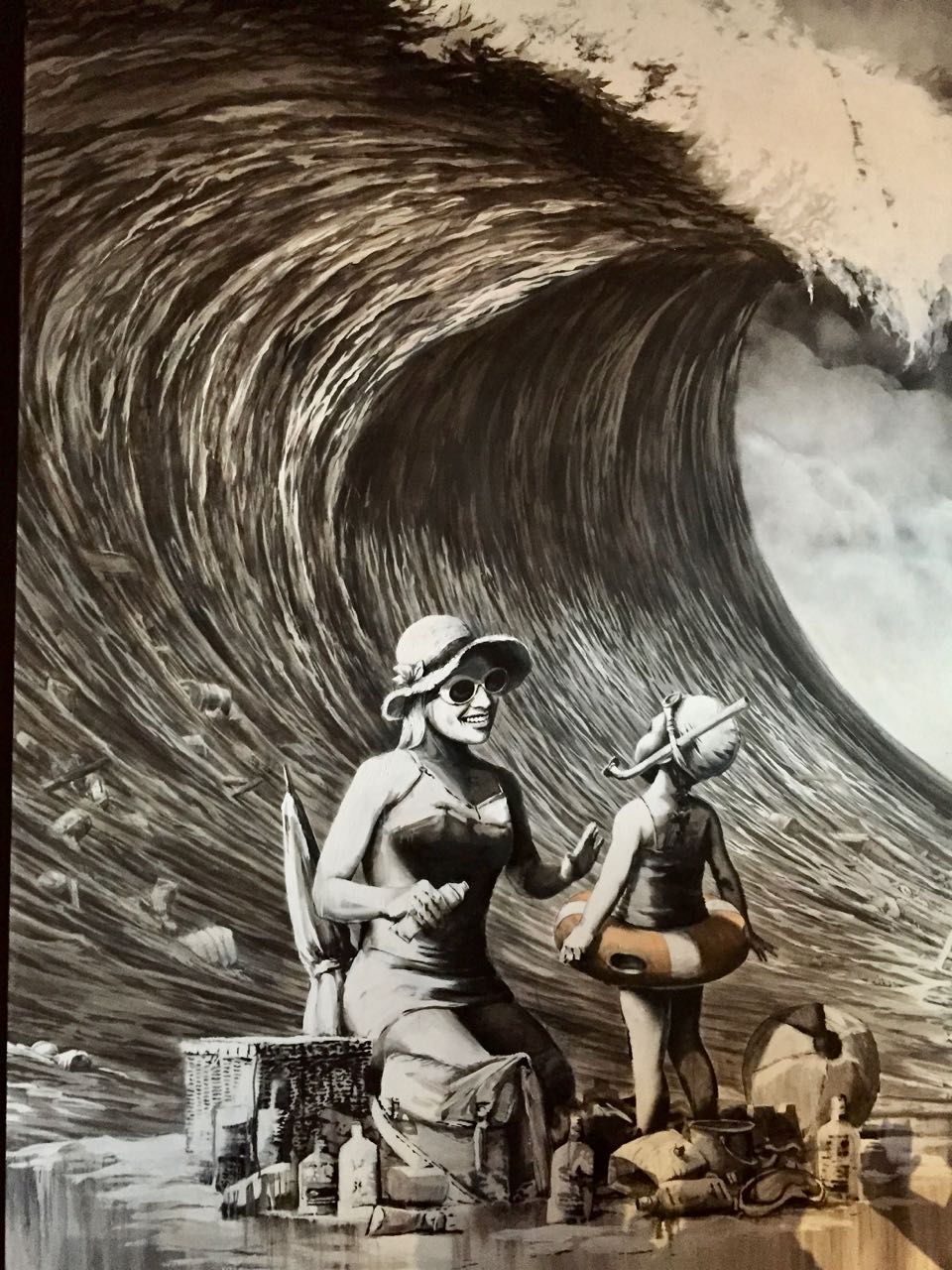

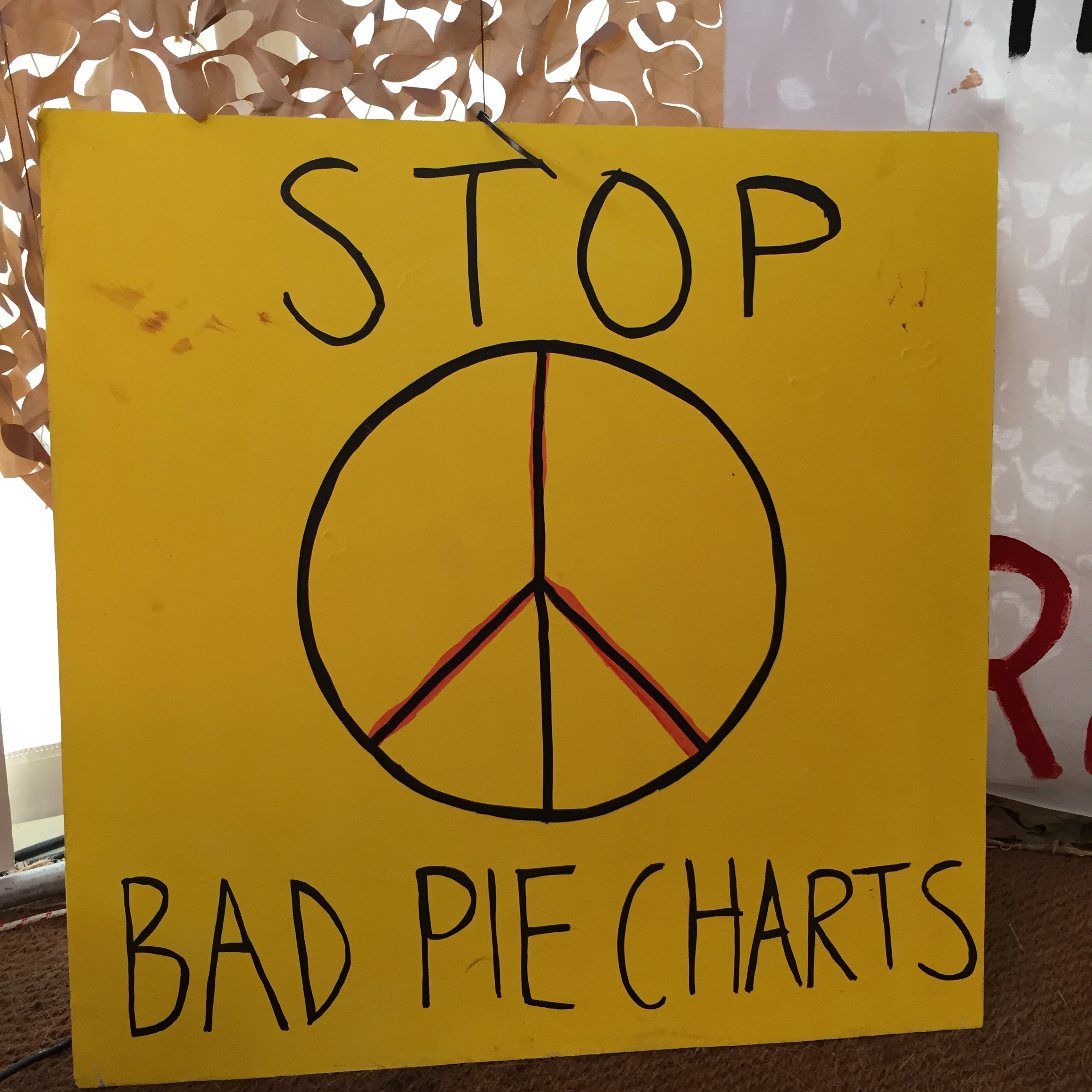

Some of Banksy’s pieces at Dismaland. Photos: R.A.

A clip from Banksy’s Grim Reaper in Bumper Car:

Who else but Banksy could have come up with the idea to train more than a hundred stewards to behave as rudely as possible at his own art show?

Photos: R.A.

Maybe the best way to get an understanding of Dismaland without having been there is through the official programme. You can download it here:

–

The Guardian published a surprisingly negative review of Dismaland on 21 August 2015:

By Jonathan Jones

The artist’s ‘Bemusement Park’ claims to be making you think, but as an actual experience it is thin, threadbare and, to be honest, quite boring

This place is unreal. A dilapidated pub, desperate-looking big wheel and grim promenade perfectly express the melancholy of the British seaside. But that’s just Weston-super-Mare on a cloudy morning. Dismaland is even stranger. Or so I hope, as I join the very first visitors to Banksy’s “Bemusement Park” waiting to see what lies behind a miserably gothic sign on the battered facade of a decaying lido.

People have been waiting for hours in a queue that stretches far along the prom. A thousand free tickets have been given away to Weston-super-Mare residents for this first public day. All ages and subcultures, from punks to a man dressed entirely in union jacks, are waiting to have their bags searched.

There are two layers of security as we pour in: real and fake. The fake security is one of the funniest moments of the day. Created by Californian artist Bill Barminski, it consists of cardboard X-ray machines and tables of cardboard objects supposedly taken from visitors. But this joke about modern security systems does not change the fact that before you enter Dismaland you do actually get your bag thoroughly inspected by very real security guards who asked one visitor if he had any knives or, get this, spray cans. All graffiti in Dismaland is official graffiti.

You can see why Banksy needs to control spontaneous art. Already the streets between the railway station and his attraction have been enlivened by rival street artists. Banksy. He’s so famous that Weston-super-Mare’s lucky golden ticket holders rush into the park already taking pictures, and I too am caught up in the thrill. This has been in the Daily Mail and everything, it’s got to be special.

Greeters – or rather, sulkers – wear Mickey Mouse ears and T-shirts that say DISMAL. Instead of being forced to smile all day they have to grimace all day. Some are so good at it they appear genuinely pissed off. It’s infectious, for me at least.

As cameraphones snap everything in sight, the gloom of the British seaside at its most dilapidated and moribund wells up in me. Memories of amusement arcades in Rhyl. Banksy has created something truly depressing. There at the heart of Dismaland is the fairytale castle, ruinous and rancid. The lake around it has a fountain that is a police water cannon. But an empty feeling is starting to hollow me out. Where’s the fun I was promised? Well, I wasn’t promised any fun, just dismalness. But surely not this dismal.

Inside the festering wreck of a fairytale castle, Cinderella’s coach has crashed. Flash bulbs create indoor lightning as paparazzi photograph her. Shock! It’s like the death of Diana. But there’s no emotion. The lifesize tableau, by Banksy himself, is just one big smirk. Wait. He’s built a castle. He leads us into it … For this? It’s such a trite, simplistic joke.

Dismaland is not all crap jokey installations, however. There are political one-liners here as well as artistic ones. People are queuing up to go inside a caravan with intense displays about the evil of our fascist police state. There is also a huge model of said fascist police state, with tiny police cars everywhere, blue lights flashing right across a diorama of a city at night.

The irony of the security on the way into Dismaland is underlined by all the references to CCTV and the wicked security establishment that pervade it. Yet that obvious double standard goes much deeper. Dismaland is a kind of consummation, for me, of all that is false about Banksy. It claims to be “making you think” and above all to be defying the consumer society, the leisure society, the commodification of the spectacle. Disneyland packages dreams, Dismaland is a blast of reality. But it is just a media phenomenon, something that looks much better in photos than it feels to be here. “Being here” is itself just a way of touching the magic of Banksy’s celebrity – that’s why everyone is taking pictures. This is somewhere to come to say you went. As an actual experience it is thin and threadbare, and I found, to be honest, quite boring.

I felt I was participating in a charade where everyone has to pretend this is a better joke than it is. In reality the crazy fairgrounds and dance tents at rock festivals are far more subversive – because they are joyous.

Perhaps you need intoxicants to enjoy Dismaland, and I was there at 11 in the morning. But its failure to create joy is self-defeating. Funfairs really are strange, wild places, as film-makers have known since Tod Browning made Freaks and rock music has known since the Doors recorded Strange Days. But in Dismaland, the rather well established idea that fairs are bizarre is not taken anywhere new or interesting.

As a news story, a media sensation, it works wonderfully – but up close, this is a Potemkin theme park. It’s not an experience, just a pasteboard substitute for one. Indeed, it is a mere art exhibition. Dismaland does not offer the energy and danger that real theme parks do. Instead, it brings together a lot of bad art by the seaside.

Banksy shows a painting of a mother and child about to be overwhelmed by a tsunami. The grotesquely clumsy crudeness of his painting technique up close, and without any excuse that he did it quickly to evade the cops, is embarrassing. But nastiest of all is the work’s peculiar lack of human feeling. We are – apparently – meant to think it’s funny that the wave is about to kill these beachgoers. They have lots of commodities, you see – sun cream and stuff. All the detritus of consumer capitalism. See the wave of the future crush them! This heartless allegory is worthy of Maoist propaganda. As art it is sterile and dead.

Banksy does better with a figure of Death riding a dodgem. This would be a lot of fun if you could go on the dodgems and try to dodge death. Sadly you just have to watch. It elicits a half laugh.

At least a visit to Dismaland is a real, sustained chance to assess Banksy as an artist. His one-dimensional jokes and polemics lack any poetic feeling. Devoid of ambiguity or mystery, everything he has created here is inert and unengaging. Cinderalla dies and no one gives a toss. What a good joke about our time, that one of the most famous critics of the way we live now is nothing more than a media-savvy cultural entrepreneur.

Banksy’s taste in other artists is no more insightful. Most of the artists he’s selected for this seaside outing are as one-dimensional as his own visions.

Only one image held me. It has been a long time since I was thrilled to see a Damien Hirst but among all the half-baked efforts here, Hirst’s gold-framed vitrine containing a unicorn has a true strangeness. It is not preachy or self righteous. Nor is its fascination easily explained. It is a real fairground attraction, freakish and bizarre. Dismaland needs a few more unicorns. So does Weston-super-Mare. So do we all.

In February 2015, Banksy published a 2-minute video titled “Make this the year YOU discover a new destination” about his trip to the Gaza Strip. During the visit to Gaza in early 2015, Banksy painted at least four exquisite works, among them a weeping Niobe, and a kitten on the remains of a house destroyed by an Israeli air strike. He also did a text-based piece, a quote from Christian philosopher Paolo Freire, of Brazilian origin: “If we wash our hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless, we side with the powerful; we don’t remain neutral. ”

In his own words, in a statement to the New York Times:

“I wanted to highlight the destruction in Gaza by posting photos on my website — but on the internet people only look at pictures of kittens . I don’t want to take sides. But when you see entire suburban neighborhoods reduced to rubble with no hope of a future — what you’re really looking at is a vast outdoor recruitment center for terrorists. And we should probably address this for all our sakes.”

Videoclip of the Gaza operation: