Between 2000 and 2005, Banksy, or one of the top guns in Team Banksy, did a number of radio interviews and at least one TV interview. And yes, it is the same person with a Bristolian accent in all of the radio interviews, as well as the TV interview below:

Severnshed Interview. BBC Bristol, March 2000

Banksy was interviewed about the London street art scene. ca 2001

The Turf War Interview by BBC. July 2003

The lost ITV interview from Turf War. ITV, July 2003

The same Banksy that was interviewed by BBC Radio at Turf War (see radio interview clip above) was interviewed the same day on camera by ITV by Haig Gordon.

The NPR Interview: All things considered

On 24 March 2005, a National Public Radio show called All Things Considered interviewed Banksy on the pranks at four New York museums that he had just done. You can listen to it here:

WRITTEN INTERVIEWS

The enemy within

The Hip Hop Connection. April 2000

Verbals & Visuals: Boyd Hill

Source: http://bristolsound.blog10.fc2.com/blog-entry-634.html

Graf culture often just plods along, writers painting piece after piece of meaningless crap. That said, there’s always a subversive waiting in the wings to really tear s**t up. Bristol artist Banksy does things differently, often to devastating effect. HHC went along to ART 2000 at the upmarket Islington Design Centre to talk strategies with the nation’s most wanted.

What influenced you to start using stencils?

“About five years ago I saw an image in a newspaper, cut it out as a stencil, then painted it in half a dozen places. Purely from the reaction I got I realised it’s all about efficiency these days. A tight image in 30 seconds is the way to go.”

What was the idea behind the piece in Poland Street, W1?

“The Poland Street piece was about the fact that artists don’t matter. You’re made to feel very aware that in this country doctors and entrepreneurs are at the top, then estate agents and plumbers, then the unemployed and slightly below them are your artists. You know, we don’t f**king matter.

“A lot of what I do is about taking the control back. The riot image is about throwing colour but in a dark way. It’s difficult to describe in words but having a balaclava on and chucking paint around is very similar to wearing a mask and throwing flowers. It’s all pest control, but it’s pests controlling them, not them controlling the pests.”

How do you view the British art scene?

“I’m not part of that scene. I never went to art college and I’m not from a family of artistic people – I never even had the connections to be part of the art world. You’ve got to be fine about it and not bitter and twisted, but I use it to my advantage and operate on a different level. Like if you put up a stencil, more people will see that as opposed to a painting in a gallery and it costs nothing to see.”

What’s the public’s reaction to your work?

“I try to get as little feedback as possible because that involves talking to people. Everyone has their own interpretation of my work. When I did the clown stencil holding handguns some people hated it and thought it scared their kids, whereas others thought it was the funniest thing out. You have to be careful who you listen to.”

How different is painting in London from Bristol?

“Well, it takes ages to get anywhere and the anti-terrorist police are a bit more edgy than in Avon & Somerset. I’d say 70 per cent of the stuff I’ve done has been cleaned. I paint for about 25 people and if anyone else likes it then cool, but if they don’t then ‘f**k you’.”

You’ve scored a few ‘hits’ in clubs. Do you find door security a problem these days?

“I did a couple of hits in Bar Rhumba and this prick comes up to me and says, ‘My brother owns this club, what are you doing?’ So I said, ‘Yeah I spoke to him about it and he was safe,’ so the guy just f**ked off and nodded. It’s like if you’re going to front, I’ll front because we can talk all about it. Clubs are good because it’s always nice to get past security, no matter who it is.”

What was it like painting in New York?

“I’ve lived in New York on and off for about two years, and last year I was asked to do a series of paintings. I did a picture of a guy sitting on a subway train, then Mickey and Minnie Mouse get on and start mugging the guy and painting graffiti all over the train. It was a comic strip and was put onto the side of the Carlton Arms Hotel as four pieces. Some people got really s**tty about it, especially they found out I was English. These two women who happened to be the wives of lawyers started a campaign to have it taken down. The New York Post ran a story on it but thankfully it stayed.”

Your canvas paintings have a very anarchic feel. Is rioting a big passion?

“I’ve been to a few and I like it when the world’s turned on its head. It’s something that taking drugs will never give you. I was in London for the Poll Tax riot in 1990 and someone put through the window of a music store and all these saxophones which cost two grand were suddenly free. It’s your graffiti writer’s dream when you run things and the police are s**t scared. I’ve got a passion for rioting and it makes good pictures.

“Canvases are for losers really. You’re looking to sell to people who are on your level and I don’t like the fact that you’re selling to people you don’t know. I like to think there’s a side of me that wants to smash the system, f**k s**t up and drag the city to its knees as it screams my name. And then there’s the other, darker side.”

Catch Banksy’s work on the streets of Bristol, London and New York City

Cheeky Monkey

The Indepeendent, early 2000

by Fiona McClymont

It all started in Bristol six years ago. Strange and slightly sinister images began appearing on city-centre walls. They’ve now spread, via New York and various British cities, to London. Take a walk around Soho and you can’t miss them. It’s all the work of one 26- year-old graffiti artist known only by his tag, “Banksy”. His work has been attracting a lot of attention, not least from the police, but despite this he’s about to stage a retrospective next week, at a secret location in London. Naturally, this won’t be at your average art gallery, but outside, on an enormous wall, on which a back- catalogue of his images will be sprayed, using his trademark stencils.

Banksy is the first to admit, “I’m doing it with a smile on my face. On the wall will be my `greatest hits’. I’ll also put some on canvases and then burn the limited-edition stencils”. Which means that something which started its life being hastily sprayed on to a wall in the middle of the night can now hang in your living room. A strange path for a graffiti artist? Not really, says Banksy. “If you want to eat and make pictures then you don’t have a lot of routes open to you.” Besides which, “The more you paint on walls, the bigger the risk, and the bigger the catalogue of criminal damage you’ve got to deal with.”

So, will the man who once graffiti’d the inside of the elephant cage at London Zoo – “I wrote, `I want out. This place is too cold. Keeper smells. Boring, boring, boring”” – be giving up street painting for a life inside the studio? He thinks not: “There’s absolutely nothing better than painting something illegally on a wall and getting away with it. Because, you’ve won.”

On the street “I use monkeys in my pictures for a lot of reasons – guerrilla tactics, cheeky monkeys, the fact that we share 98.5 percent of our DNA with them. If I want to say something about people I use a monkey. If you use a person in an image, then you have to use a specific type, so you’re either picking on someone young, old, or whatever. I painted the clown with a gun (above left) near a roundabout in Bristol, where two lanes of traffic had to slow down. It’s at such a height on the wall that it appears 3-D to the cars in the outside lane – it looks like it’s coming over the bonnets towards them. That’s what it’s all about, impact. The rats (left) are just tiny, mischievous hits. I’ve called them `electronic tagging’ – they’re electronically controlled and `tagging’ is the graffiti term to describe writing your name all over the place. They’re on walls all over London at ground level, as if they’re running along the floor.”

In the studio “When I get lit up by an image or an idea, I make it straightaway and then go out and paint it. Taking time on something is not necessarily helpful. The days of wandering around casually with a spray can in your bag are over – the more sophisticated the police get, the quicker and more ruthlessly you have to work. One of the reasons I use stencils is that they’re very efficient – you have to split everything into black or white and eliminate all grey areas, it’s a very good way to live your entire life by, in fact. I’ve burnt most of the ones I’ve made, because they are extremely incriminating evidence. The whole process you have to go through to paint – building yourself up to it, the paranoias, the tricks, the waiting – is dark and twisted and it’s hard; it’s a lot of stress just to put colour on a wall.”

You can view Banksy’s work at his website http://www.banksy.co.uk and for details of the forthcoming show contact info@freewheelinmedia.com

Painting and decorating

by Si Mitchell and Simon Chapman

Metaphysical Graffiti

Squall. August 2000

A chat with Banksy

Big Daddy Magazine, Issue 7. 2001

by Shok-1

I should count myself lucky I wasn’t blindfolded like the reporter from The Face magazine on the way to the secret HQ of Banksy [apparently he enjoyed it. Each to his own!]

Not easily categorised, the man is an unusual blend of aerosol attitude and fine art. Some narrow-minded purists have found his stencil based work hard to swallow, but the establishment can’t seem to get enough.

Sitting amongst huge piles of street level photos and crisp canvases alike we caned caffeine and talked shop. This is not an interview but just a conversation with a normal bloke with big dreams…

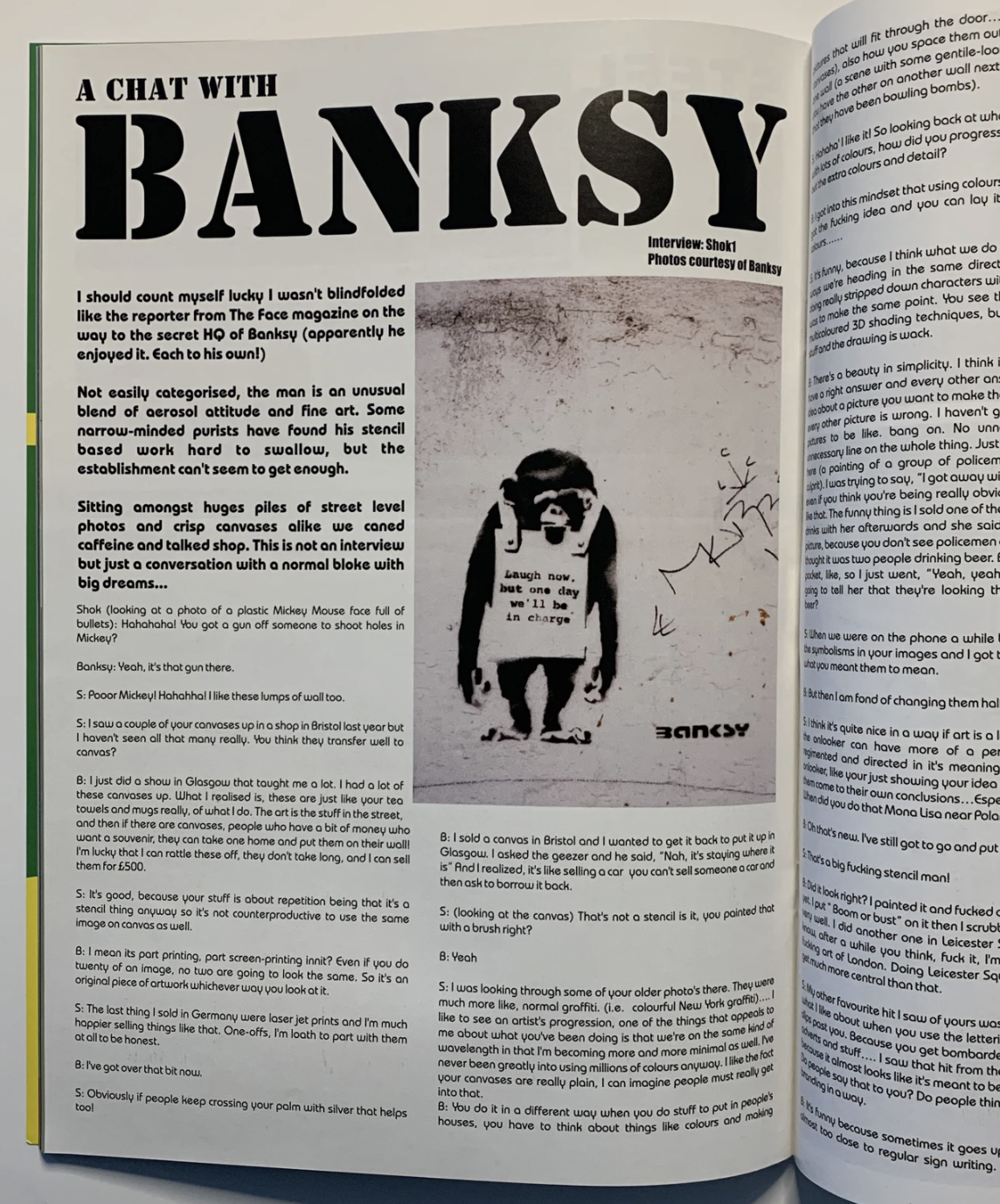

[looking at a photo of a plastic Mickey Mouse face full of bullet holes] Hahaha! You got a gun off someone to shoot holes in Mickey?

Yeah, it’s that gun there.

Pooor Mickey! Hahaha! I like these lumps of wall too. I saw a couple of your canvases up in a shop in Bristol last year but I haven’t seen all that many really. You think they transfer well to canvas?

I just did a show in Glasgow that taught me a lot. I had a lot of these canvases up. What I realized is, these are just like your tea towels & mugs really, of what I do. The art is the stuff in the street, and then if there are canvases, people who have a bit of money who want a souvenir, they can take one home and put them on their wall! I’m lucky that I can rattle these off, they don’t take long, and I can sell them for 500.

It’s good, because your stuff is about repetition being that it’s a stencil thing anyway so it’s not counterproductive to use the same image on a canvas as well.

I mean it’s part printing, part screen-printing innit? Even if you do twenty of an image, no two are going to look the same. So it’s an original piece of artwork whichever way you look at it.

The last thing I sold in Germany were laser jet prints and I’m much happier selling things like that. One-offs, I’m loathe to part with them at all to be honest.

I’ve got over that bit now.

Obviously if people keep crossing your palm with silver that helps too!

I sold a canvas in Bristol and I wanted to get it back to put it up in Glasgow. I asked the geezer and he said, “Nah, it’s staying where it is” and I realized, it’s like selling a car – you can’t sell someone a car and then ask to borrow it back.

[Looking at the canvas] That’s not a stencil is it, you painted that with a brush right?

Yeah.

I was looking through some of your older photos there. They were much more like, normal graffiti. [i.e. colourful New York graffiti]… I like to see an artist’s progression, one of the things that appeals to me about what you’ve been doing is that we’re on the same kind of wavelength in that I’m becoming more and more minimal as well. I’ve never been greatly into using millions of colours anyway. I like the fact your canvases are really plain, I can imagine people must really get into that.

You do it in a different way when you do stuff to put in people’s houses, you have to think about things like colours and making pictures that will fit through the door… [getting out a matching set of canvases] also how you space them out is interesting. You have one on one wall … then you have the other on another wall next to it [the second canvas shows that they have been bowling bombs].

Hahaha’ I like it! So looking back at when you were doing the big walls with lots of colours, how did you progress onto the stencilling and leaving out the extra colours and detail?

I got into this mindset that using colours is a sign of weakness, if you’ve got the fucking idea and you can lay it down, you don’t need lots of colours……

It’s funny, because I think what we do is really different, but in a lot of ways we’re heading in the same direction. The reason why I started doing really stripped down characters with just one colour and an outline was to make the same point. You see these kids with these incredible multi colored 3D shading techniques, but you strip away all the flashy stuff and the drawing is wack.

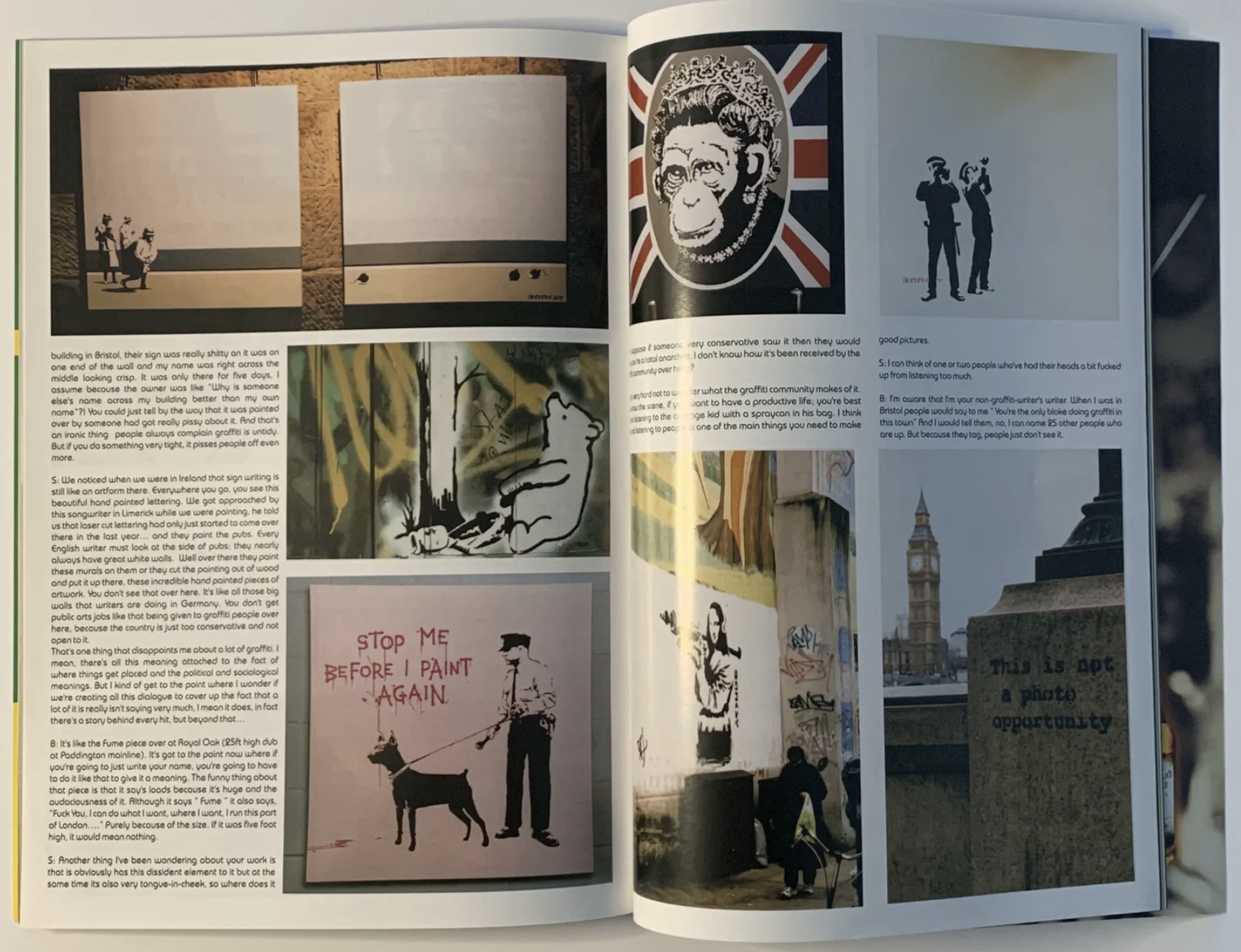

There’s a beauty in simplicity. I think it’s a bit like maths, in that you have a right answer and every other answer is wrong. If you’ve got an idea about a picture you want to make there is a perfect picture for it and every other picture is wrong. I haven’t got there yet, but I want all my pictures to be like. bang on. No unnecessary colour, not a single unnecessary line on the whole thing. Just perfect. Like with this cop thing here [a painting of a group of policemen looking hopelessly for the culprit]. I was trying to say, “I got away with it” in as few lines as possible, even if you think you’re being really obvious, it doesn’t always work out like that. The funny thing is I sold one of these to this bird, I had a couple of drinks with her afterwards and she said, “I’m really pleased with that picture, because you don’t see policemen getting drunk do you?” She thought it was two people drinking beer. But I already had the cash in my pocket, like, so I just went, “Yeah, yeah sure”. I thought, is someone going to tell her that they’re looking through binoculars not drinking beer?

When we were on the phone a while back and I was trying to guess the symbolisms in your images and I got them all completely different to what you meant them to mean.

But then I am fond of changing them halfway through myself!

I think it’s quite nice in a way if art is a little bit open-ended. That way the onlooker can have more of a personal involvement. If it’s too regimented and directed in its meaning then it almost excludes the onlooker, like you’re just showing your idea at them. Maybe it’s good to let them come to their own conclusions… Especially if the art is at street level. When did you do that Mona Lisa near Poland Street?

Oh that’s new. I’ve still got to go and put the lyrics on that.

That’s a big fucking stencil man!

Did it look right? I painted it and fucked off so I haven’t even looked at it yet. I put “Boom or bust” on it but then I scrubbed it off because it didn’t read very well. I did another one in Leicester Square on the same day. You know, after a while you think, fuck it, I’m in London, let’s take it to the fucking art of London. Doing Leicester Square was satisfying, you can’t get much more central than that.

My other favourite hit I saw of yours was the Centre Point one. I tell you what I like about when you use the lettering on its own is that it almost slips past you. Because you get bombarded with so much typography in adverts and stuff…. I saw that hit from the car and I had to double-take because it almost looks like it’s meant to be there, like some official thing. Do people say that to you? Do people think the logo’s like… well I guess branding in a way.

It’s funny because sometimes it goes up so quick and so nice that it’s almost too close to regular signwriting. I did one on the side of this building in Bristol, their sign was really shitty and it was on one end of the wall and my name was right across the middle looking crisp. It was only there for five days, I assume because the owner was like, “Why is someone else’s name across my building better than my own name?!” You could just tell by the way that it was painted over someone had got really pissy about it and that’s an ironic thing – people always complain graffiti is untidy, but if you do something very tight, it pisses them off even more.

We noticed when we were in Ireland that sign writing is still like an artform there. Everywhere you go, you see this beautiful hand painted lettering. We got approached by this sign-writer in Limerick while we were painting, he told us that laser-cut lettering had only just started to come over there in the last year… and they paint the pubs. Every English writer must look at the side of pubs; they nearly always have great white walls. Well over there they paint these murals on them or they cut the painting out of wood and put it up there, these incredible hand-painted pieces of artwork. You don’t see that over here. It’s like all those walls that writers are doing in Germany.

You don’t get public art jobs like that being given to graffiti people over here, because the country is just too conservative and not open to it. That’s one thing that disappoints me about a lot of graffiti.

I mean, there’s all this meaning attached to the fact of where things get placed and the political and sociological meanings, but I kind of get to the point where I wonder if we’re creating all this dialogue to cover up the fact that a lot of it really isn’t saying very much, I mean it does, in fact there’s a story behind every hit, but beyond that…

Banksy It’s like the Fume piece over at Royal Oak [25 foot high dub at Paddington mainline]. It’s got to the point now where if you’re going to just write your name, you’re going to have to do it like that to give it a meaning. The funny thing about that piece is that it says loads because it’s huge and the audaciousness of it. Although it says, “Fume” it also says, “fuck you, I can do what I want, where I want, I run this part of London…” Purely because of the size. If it was 5 foot high, it would mean nothing.

Another thing I’ve been wondering about your work is that it obviously has this dissident element to it but at the same time it’s also very tongue-in-cheek, so where does it fit? I suppose if someone very conservative saw it then they would think you’re a total anarchist. I don’t know how it’s been received by the graffiti community over here?

I try very hard not to wonder what the graffiti community makes of it. You know the scene, if you want to have a productive life; you’re best off not listening to the average kid with a spraycan in his bag. I think not listening to people is one of the main things you need to make good pictures.

I can think of one or two people who’ve had their heads a bit fucked up from listening too much.

I’m aware that I’m your non-graffiti writer’s writer. When I was in Bristol people would say to me, “You’re the only bloke doing graffiti in this town” and I would tell them, no, I can name 25 other people who are up, but because they tag, people just don’t see it.

So many people are street bombing now and it’s been going around for so long that the public are desensitised to it I think. It’s like constant background noise, it doesn’t get their attention like it used to. I was really into street bombing for around six years. Then I thought, OK, I’ve been up for years, who gives a shit about seeing my name? So What? I thought, What am I doing now that I haven’t already done? I mean, obviously you do it for other writers to see, but I want more people to pay attention to it than that.

If you want to get up in a major way today, you need to be original rather than prolific, like most things it’s quality over quantity. This “Graffiti Area” stencil is without a doubt the best thing I’ve done, because it’s introducing the X-Factor – a load of shit you have no control over. I put the stencil up and a week later kids have written everywhere all over the wall. I spoke to this Lawyer and he reckoned in his experience that it would be enough of a defence if you were a kid and got picked up by the old bill writing on one of these walls. That would give you enough, ‘reasonable doubt’ to beat the case. The National Highways Agency doesn’t exist and the official crest on it is off a packet of Benson & Hedges. It’s a complete Mickey Mouse thing.

But it’s enough for them to say they didn’t think they were doing anything wrong.

And the amazing thing is, if one kid gets off like that, it sets a precedent. That’s what I’m up for now. I’m going to put up 500 of those fuckers and then wait until it ends up in court and see what happens. It’s quite political, because it means you have the right to go out into your community and say how you think it should look, and that you can potentially bypass parliament and change laws.

I mean, you could sit there and say that you think it would be better if we allowed more public art in this country. Then you could complain about it. Then you could try and get the council involved.

Or you could just put up notices in the middle of the night saying, “You are allowed to paint this wall” and bypass the system. Get a test case and you can potentially get into the statute books.

I just read an interview with Dean from Brighton. He’s been using standard graffiti format, just straight letter “Dean” pieces but the difference is that he has really well thought out ideas about where to put them and why. He’s using it to oppose the gentrification going on in Brighton by preventing them from making it into a sanitized, untouched environment.

I’ve got a copy of Big Daddy #6 for you here…

Who did this cover?

I did.

Bit different for you isn’t it?

Well what’s the point of just doing things you know you can do? You have to keep moving on… What’s this stencil made out of card?

Yeah, it was funny the other day, I was putting up that Mona Lisa and this guy keeping lookout was in hysterics because it was really papery card and part of the bazooka kept falling off.

He thought I would have cut them out of resin and all kinds of things. A big part of the thing for me is the fact that I’ve only ever used card that was free. I can get a can for 60p, that’s good for 30 stencils and then the cost of a couple of disposable blades and that’s it. It’s really important to me that you can have a huge street campaign that could get you famous in a month if you went nuts, and it would cost you about a tenner, the money factor is what turns me off the gallery circuit, that it costs so much to mount a show. Still, you can have a show that costs you next to nothing, like London, under the bridge. Our deal with that was that we nicked all the materials except for about four pounds worth of black paint.

How many people showed up?

On the opening night, about 500 people. We let people know in advance when it was going to happen, told them that they would have to email this address to find out where it was going to be at the last minute because it was all illegal. Six months later Cargo opened their club next to it and the artwork is still up. People have written on it, but the people from the club took a brush and carefully whited all the tags and left the stencils.

I see quite a lot of commercially orientated stencils around London. Was that here when you moved in?

Nah. Have you seen the [name removed to avoid undue promotion] ones? They’re everywhere. I saw them in Glasgow and I was lining them out, because they approached me when I first came to London and asked me to do stuff for them for free, even though they’ve got backing.

You seem quite solitary in the way you do things…

If there was someone on the same wavelength I would maybe join up and do some things. When I used to do big pieces, I would always do them on my own. One time I went out, I had a friend who was looking out for me. I just started painting a big piece and he goes, “I’ve got a really bad feeling about this”. That ruined the whole mission from the word go. I have a project planned with Dane, but I’m going to carry on doing this mostly by myself.

Something to Spray

The Guardian, July 17, 2003

By Simon Hattenstone

You may not have heard of him, but you’ve probably seen his work. From policemen with smiley faces to the Pulp Fiction killers firing bananas, Banksy’s subversive images are daubed on walls everywhere – and now he’s putting on an exhibition. Simon Hattenstone meets Britain’s No 1 graffiti artist.

Banksy is due any minute. The only trouble is I don’t know what he looks like. Nobody here seems to know what he looks like. But they all know him. That is, they know of him. That is, if he is a he. The barman in the pub in Shoreditch, a trendy part of London with a whiff of the old East End, flushes when I mention Banksy and talks in a hushed voice. “Yes, I know Bansky. Well I used to, sort of. See, I’m from Bristol, and I was also involved in graffiti.”

Is he in the pub at the moment? He shakes his head diffidently. He is not sure he would recognise him and if he did manage to point him out, thinks he could get into trouble. I tell him that I’m here to interview him. He doesn’t believe me – Banksy doesn’t do interviews. But he has agreed to one this time, though he laughs when we suggest a photograph.

Banksy is Britain’s most celebrated graffiti artist, but anonymity is vital to him because graffiti is illegal. The day he goes public is the day the graffiti ends.

His black and white stencils are beautiful, witty and gently subversive: policemen with smiley faces, rats with drills, monkeys with weapons of mass destruction (or, when the mood takes him, mass disruption) little girls cuddling up to missiles, police officers walking great flossy poodles, Samuel Jackson and John Travolta in Pulp Fiction firing bananas instead of guns, a beefeater daubing “Anarchy” on the walls. He signs his pieces in a chunky, swirling typeface. Sometimes there are just words, in the same chunky typeface – puns and ironies, statements and incitements. At traditional landmarks, he often signs “This is not a photo opportunity”. On establishment buildings he may sign “By Order National Highways Agency This Wall Is A Designated Graffiti Area”. (Come back a few days later, and people will have obediently tagged the wall.)

Banksy has branched out recently – he designed the cover of the Blur album, Think Tank, and tomorrow is the opening night of Turf War, his first gallery show in Britain. He is somehow managing to straddle the commercial, artistic and street worlds.

It is easy to become addicted to his work. Since spotting my first few Banksies, I have been desperately seeking out more. When I do come across them, surreptitiously peeping out of an alley or boldy emblazoned on a wall, I find it hard to contain myself. They feel personal, as if they are just for me, and they feel public as if they are a gift for everyone. They make me smile and feel optimistic about the possibilities of shared dreams and common ownership.

On the Banksy trail I meet lots of devotees. They tell me how he comes by stealth in the night, how he has look-outs posted while he works, how his first exhibition will be in a warehouse though only the number of the road (475) is known and not the road itself. They say that Banksy has customised the city, reclaimed it, made it theirs.

There is still no sign of him. I walk into the street to phone Steve, his “agent”. “Ah, I’ll bring him over right now,” he says in his Bristol burr. I have the strange sensation of hearing him in stereo. I look up the road, and see a man 40 yards away talking into the phone. Steve doesn’t look like an agent. Actually, he says, he is Banksy’s friend and takes photos for him.

Two minutes later they arrive in the pub. Bansky is white, 28, scruffy casual – jeans, T-shirt, a silver tooth, silver chain and silver earring. He looks like a cross between Jimmy Nail and Mike Skinner of the Streets. He asks if he can nab a cigarette and orders a pint of Guinness. There is something on his mind. He tells me how he noticed that a piece of his graffiti has been papered over by a poster advertising Michael Moore’s Stupid White Men – a bestselling book about how to subvert the system. “So Michael Moore was the corporate who fucked me over and ruined my picture. It’s a weird world, a sick world.” But he seems to quite like the idea.

Banksy started doing graffiti when he was a miserable 14-year-old schoolboy. School never made sense to him – he had problems, was expelled, did some time in prison for petty crime, but he doesn’t want to go into details.

Graffiti, he says, made him feel better about himself, gave him a voice. And Bristol had a thriving graffiti culture. “But because I was quite crap with a spray can, I started cutting out stencils instead.” I tell him about the time I graffito’d someone’s name across the road. He nods, approvingly. “Ah, that’s the key to graffiti, the positioning.” I tell him that I felt guilty – not because I had broken the law but because I had used a can of paint to get revenge and the boy had to live with his name Duluxed across the road.

“Yeah, it’s all about retribution really,” he says. “Just doing a tag is about retribution. If you don’t own a train company then you go and paint on one instead. It all comes from that thing at school when you had to have name tags in the back of something – that makes it belong to you. You can own half the city by scribbling your name over it.”

As he talks, it strikes me that he may not be who he says he is. How do I know you are Banksy? “You have no guarantee of that whatsoever.” But he seems too passionate about his work not to be. What is his real name? “Pass! You must be kidding.”

Does he consider himself an artist? “I don’t know. We were talking about this the other day. I’m using the word vandalism a lot with the show. You know what hip-hop has done with the word ‘nigger’ – I’m trying to do that with the word vandalism, bring it back.” He also likes the word brandalism.

Banksy’s attitude to brands is ambivalent – like Naomi Klein, he opposes corporate branding and has become his own brand in the process. Now, people are selling forged Banksies on the black market or stencil kits so we can produce our own Banksies. Does he mind being ripped off? “No,” he says. “The thing is, I was a bootlegger for three years so I don’t really have a leg to stand on.”

That was what was so strange about working with Blur, he says. “It was weird because I must have worked a good dozen Blur shows in the past.” Did he tell them? “Not until well into the job. I said I’ve never been inside a Blur gig, because I was with five scallies in the car park banging out posters and T-shirts of you lot. So I did the job, and basically I spunked all the money on the new thing that I’m doing – BOGOF sculpture. It’s based on Tesco’s Buy One, Get One Free. I’m making sculptures, two of each. One I sell and the other one I give away free to the city. The first one, which is going to be unveiled today, is like a huge The Thinker by Rodin, in bronze, with the traffic cone on his head also cast out of bronze.”

That is another aspect of art he says interests him – efficiency. Why spend years on a sculpture when you can simply plonk a traffic cone on the head of a classic sculpture and create a whole new work? “If you have a statue in the city centre you could go past it every day on your way to school and never even notice it, right, but as soon as someone puts a traffic cone on its head, and you’ve made your own sculpture and it’s taken seconds. The holy grail is to spend less time making the picture than it takes people to look at it.” He smiles. I’m not sure that he really believes this.

Is it true that his prints sell for upwards of £10,000? He is not sure because he doesn’t flog them directly but yes, they go for a high price. What about the story that he designed a swish New York hotel? “Well, I did paint a hotel in New York City once. But it’s a dive hotel – $68 a night. Every room is painted by a different artist and if you paint it you stay there rent free.”

Over the past couple of years the very brands he despises have approached him to do advertising campaigns for them. Is there work he would turn down on principle? “Yeah, I’ve turned down four Nike jobs now. Every new campaign they email me to ask me to do something about it. I haven’t done any of those jobs. The list of jobs I haven’t done now is so much bigger than the list of jobs I have done. It’s like a reverse CV, kinda weird. Nike have offered me mad money for doing stuff.” What’s mad money? “A lot of money!” he says bashfully.

Why did he turn it down? “Because I don’t need the money and I don’t like children working their fingers to the bone for nothing. I like that Jeremy Hardy line: ‘My 11-year-old daughter asked me for a pair of trainers the other day. I said, ‘Well, you’re 11, make ’em yourself.’ I want to avoid that shit if at all possible.”

I ask him if you need to be nimble to be a good graffiti artist. “Yeah, it’s all part of the job description. Any idiot can get caught. The art to it is not getting picked up for it, and that’s the biggest buzz at the end of the day because you could stick all my shit in Tate Modern and have an opening with Tony Blair and Kate Moss on roller blades handing out vol-au-vents and it wouldn’t be as exciting as it is when you go out and you paint something big where you shouldn’t do. The feeling you get when you sit home on the sofa at the end of that, having a fag and thinking there’s no way they’re going to rumble me, it’s amazing… better than sex, better than drugs, the buzz.”

He talks about the fun he had at Glastonbury this year. “The police seemed to feel very relaxed, and they were driving Land Rovers. We found two parked up with the cops out chatting to girls on the main drag and I nearly always carry a can of paint, so I just walked up and did a random swiggle on the side of one, and then handed the can of paint to my friend who wrote ‘Hash for cash’ on the side of another. By the end of that night, we had done seven police vehicles with aerosol.” He says he has been arrested for graffiti in the past, but not in recent years, and never as Banksy.

Was it a tough decision to exhibit in a gallery? No, he says – first of all, this is hardly a posh gallery, it’s an old warehouse. Second, without a formal space, how could he possibly display his live sheep, pigs and cows? Actually, he says, graffiti is by definition rather proscriptive. “Most councils are committed to removing offensive graffiti within 24 hours, anything racist, sexist or homophobic, they will send out a team within 24 hours.” But somehow if it’s “art” in a gallery, the boundaries of taste aren’t so rigidly defined.

He talks about his stencils of Jewish women at Belsen, daubed in fluorescent lipstick – an image as poignant as it is grotesque. “Now I could never do that on the street because it’s just blatantly offensive.” But in a gallery he can show it in context. “It’s actually based on a diary entry from a colonel who liberated Bergen-Belsen. He described how they liberated this women-only camp, and a box of supplies turned up containing 400 sticks of lipstick, and he went nuts – ‘Why are you sending me lipstick?’ But he sent it out to the women, and they put it on each other, they did their hair; and because it gave them the will to live it was probably the best thing the soldiers did when they liberated that camp.” He tells the story beautifully. “See, that’s talking about how the application of paint can make a difference.”

Does he ever see himself becoming part of the art establishment? “I don’t know. I wouldn’t sell shit to Charles Saatchi. If I sell 55,000 books [he has published two, Existencilism and Banging Your Head Against A Brick Wall] and however many screen prints, I don’t need one man to tell me I’m an artist. It’s hugely different if people buy it, rather than one fucking Tory punter does. No, I’d never knowingly sell anything to him.”

He returns to the subject of the opening night, and talks about it with such excitement. “A part of me wishes I could go because I’ve put together a really nice setup.”

But, he says, it would be too risky. Will his parents be there? He shakes his head. “No. They still don’t know what I do.” Really, I say, they have no sense of how much you’ve achieved? “No,” he says tenderly. “They think I’m a painter and decorator.”

Art Attack

Wired Magazine. August 01, 2005

By Jeff Howe

https://www.wired.com/2005/08/bansky/?_sp=9f711b29-f7ed-4acd-9297-0167b89a0adf.1742677513718

First he turned back alleys into galleries. Then he hacked the MoMA and the Met. Meet Banksy, the most wanted man in the art world.

It’s noon in London, and self-described “art terrorist” Banksy is preparing for his next installation. “I’ve created a cave painting,” he says. “It’s a bit of rock with a stick man chasing a wildebeest and pushing a shopping cart.” The next day, Banksy carefully hangs his work – called Early Man Goes to Market and credited to “Banksymus Maximus” -in Gallery 49 of the venerable British Museum, accompanied by a few sentences of explanatory text. He does this without the knowledge or consent of museum officials; they learn about the latest addition to the collection only after Banksy announces it on his Web site.

Over the past few years, Banksy has emerged as an ingenious and dexterous culture jammer, adept at hacking the art world and rewriting its rules to suit his own purposes. He once closed a tunnel in London while he and his friends, disguised as overall-clad painters, whitewashed the walls. Then Banksy applied his own distinctive black stencils on the newly cleaned surface. “We called our friends, bought some beer, and staged a ‘gallery show,'” he says with a chuckle. Last March, Banksy achieved a sort of art world quadruple crown when he snuck his works into four New York City museums – the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Brooklyn Museum – in a single day. Such feats have earned him worldwide media attention and the kind of rewards traditional artists would kill for, including an offer from Nike to work on an ad campaign (he declined) and an invitation to do a public painting for the 2004 Liverpool biennial (he accepted). The British Museum even added Early Man Goes to Market to its permanent collection.

Brits have come to expect daring stunts from Banksy, who uses a pseudonym to avoid arrest for past escapades. But critics see him as nothing more than an overhyped vandal. Peter Gibson, a spokesperson for the Keep Britain Tidy campaign, says graffiti has become an epidemic: “How would he feel if someone sprayed graffiti all over his house?” Banksy says his work is merely “cheeky.” And it’s true, the pieces are long on humor: The one Banksy smuggled into the MoMA was a painting of a cheap brand of British tomato soup, a send-up of Andy Warhol’s iconic can of Campbell’s. But his arsenic-tinged wit has a purpose: By hijacking the established system of art exhibition, Banksy is drawing attention to its shortcomings. “Art’s the last of the great cartels,” he contends. “A handful of people make it, a handful buy it, and a handful show it. But the millions of people who go look at it don’t have a say.” Most of Banksy’s work isn’t found inside any building at all. “I don’t do proper gallery shows,” he says. “I have a much more direct communication with the public.”

Born in Bristol in 1974, Banksy started his career at 14 as a standard-issue spray-paint vandal before switching to stencils. “I wasn’t good at freehand graffiti,” he says. “I was too slow.” Soon Banksy had made a (fake) name for himself with wry images like schoolgirls cradling atom bombs, British bobbies caught snogging, and Mona Lisa shouldering a rocket launcher. These paintings contrast sharply with the usual all-but-unreadable scrawls. “Most graffiti is like modern art, isn’t it?” he says. “People are like, What does it mean?”

Banksy’s messages are far more accessible. He once painted a thought bubble on the wall of the elephant pen at the London Zoo: “I want out. This place is too cold. Keeper smells. Boring, boring, boring.” The difficulty of that job gained the respect of the graffiti community but, more than that, it caught the imagination of the public, which was happy to empathize with the elephants.

Banksy has a thing for animals. In much of his graffiti they serve as thinly veiled stand-ins for humans. Rats, that other species struggling to subsist in our dirty, dangerous cities, show up a lot. Armed with radio transmitters, personal flying devices, and, natch, paintbrushes, many seem to be waging a covert war against some unidentified authority. One image depicts a rat swept up in the melody of its own violin-playing, trying, it seems, to carve a bit of art out of a sterile environment.

Which is pretty much Banksy’s mission, too. Noting that he’s not without altruistic impulses – “I always wanted to be a fireman, do something good for the world” – Banksy says he wants to “show that money hasn’t crushed the humanity out of everything.”

Banksy The Naked Truth

Swindle Magazine, Issue 8, 2006

By Shepard Fairey

One of the most inappropriate nicknames of all time, at least in my opinion, belonged to Ronald Reagan: “The Great Communicator,” who we’ve come to learn did a pretty shitty job of communicating the government’s problems and indiscretions. A nickname like that deserves a more righteous, honest owner—someone like Banksy.

Most people think of art as a way of conveying emotions, as opposed to language, the means by which we express ideas. Whatever line there is distinguishing art and language, Banksy paints over it to make it disappear, then stealthily repaints it in the unlikeliness of places. His works, whether he puts them on the streets, sells them in galleries, or hangs them in museums on the sly, are filled with imagery tweaked into metaphors that cross all language barriers. The images are brilliant and funny, yet so simple and accessible that even children can find the meaning in them: even if six-year-olds don’t know the first thing about culture wars, they have no trouble recognizing that something is amiss when they see a picture of the Mona Lisa holding a rocket launcher. A lot of artists can be neurotic, self-indulgent snobs using art for their own catharsis, but Banksy distances himself from his work, using art to plant the feelings of discontent and distrust of authority that anyone can experience when he prompts them to ask themselves one gigantic question: Why is this wrong? If it makes people feel and think, he’s accomplished his goal.

Banksy’s work embodies everything I like about art and nothing I dislike about it. His art is accessible rather than elitist, since he does it on the street; it has a powerful political message that’s conveyed with a sense of humor, which certainly makes the bitter pill easier to swallow; it’s pleasing to look at, because it’s technically very strong but not overly complex and intimidating; and he pulls it off in such a way that its presence in its context communicates not only his message but his dedication to effecting the change he promotes in that message, whether he’s defying Israeli hegemony by painting the separation wall in Palestine or bypassing the elitist review board of a museum by hanging his work himself. He definitely has his share of critics, who say that he burns too many bridges by rejecting countless opportunities to gain money or fame, but he simply has no interest in doing anything that falls outside his goal of making provocative, powerful artwork. He’s a good friend and a tremendous source of inspiration; he’s The Great Communicator of our time, and the most important living artist in the world.

Shepard Fairey: How long are you going to remain anonymous, working through the medium itself and through your agent as a voice for you?

Banksy: I have no interest in ever coming out. I figure there are enough self-opinionated assholes trying to get their ugly little faces in front of you as it is. You ask a lot of kids today what they want to be when they grow up, and they say, “I want to be famous.” You ask them for what reason and they don’t know or care. I think Andy Warhol got it wrong: in the future, so many people are going to become famous that one day everybody will end up being anonymous for 15 minutes. I’m just trying to make the pictures look good; I’m not into trying to make myself look good. I’m not into fashion. The pictures generally look better than I do when we’re out on the street together. Plus, I obviously have issues with the cops. And besides, it’s a pretty safe bet that the reality of me would be a crushing disappointment to a couple of 15-year-old kids out there.

What got you into graffiti? I know that you did more traditional graffiti at one point.

I come from a relatively small city in southern England. When I was about 10 years old, a kid called 3D was painting the streets hard. I think he’d been to New York and was the first to bring spray painting back to Bristol. I grew up seeing spray paint on the streets way before I ever saw it in a magazine or on a computer. 3D quit painting and formed the band Massive Attack, which may have been good for him but was a big loss for the city. Graffiti was the thing we all loved at school – we all did it on the bus on the way home from school. Everyone was doing it.

What’s your definition of the word “graffiti”?

I love graffiti. I love the word. Some people get hung up over it, but I think they’re fighting a losing battle. Graffiti equals amazing to me. Every other type of art compared to graffiti is a step down—no two ways about it. If you operate outside of graffiti, you operate at a lower level. Other art has less to offer people, it means less, and it’s weaker. I make normal paintings if I have ideas that are too complex or offensive to go out on the street, but if I ever stopped being a graffiti writer I would be gutted. It would feel like being a basket weaver rather than being a proper artist.

Who are some of your favorite graffiti artists?

My favorite graffiti is done by people that aren’t in books. I’m really into the amateurs, the people who just come out of nowhere with a marker pen and write one funny thing for one night and then disappear.

“Street art” has been the cool buzzword, and artists have obtained instant credibility from these new fly-by-night galleries, skate companies wanting to do a new street art t-shirt series, whatever. All these people are picking artists that deserve to be picked and have really done work on the streets for 10 to 15 years, but then they also pick a lot of artists that have been doing something for four to six months and built themselves a nice little website. Where do you see yourself fit into that? If the pedestrians at these companies don’t really know who’s done what, how do you separate yourself from that?

Most graffiti writers arrive at a style by the need to work fast and quiet. If you arrived at a style by painstakingly drawing in your bedroom and touching up on Photoshop, then people can smell the difference from about five miles away.

How do you decide what commercial projects to work on?

I’ve done a few things to pay the bills, and I did the Blur album. It was a good record and it was quite a lot of money. I think that’s a really important distinction to make. If it’s something you actually believe in, doing something commercial doesn’t turn it to shit just because it’s commercial. Otherwise you’ve got to be a socialist rejecting capitalism altogether, because the idea that you can marry a quality product with a quality visual and be a part of that even though it’s capitalistic is sometimes a contradiction you can’t live with. But sometimes it’s perfectly symbiotic, like the Blur situation.

I’m sure you get offered jobs left and right. Are there things that you think about doing that you don’t do, or things that you wish you would’ve done?

I don’t do anything for anybody anymore, and I will never do a commercial job again. In some ways it’s a shame, cuz I’m sure I’d have had a good time doing posters for that frozen yogurt company in Hawaii and now I’d have friends I could go visit on the other side of the world. But it’s part of the job to shut the fuck up and not meet people. I never go to the openings of my shows, and I don’t read chat rooms or go on MySpace. All I know about what people think of my gear is what a couple of my friends tell me, and one of them always wants to borrow money, so I’m not sure how reliable he is.

I think there’s a lot to be said for the fine line between second guessing yourself and respecting a dialogue with people whose opinions you trust, or even people that are great because they don’t know shit about art and you get the most honest reaction from them. Because so many artists, they worry about what trends are happening in art and design and street art, they read too many magazines, and they are too wrapped up in everything; they’re paralyzed.

What’s the most perfect non-traditional piece of art that you’ve seen that’s not currently hanging in a museum?

The most perfect piece of art I saw in recent times was during an anarchist demonstration in London a couple of years ago. Someone cut a strip of turf from the grass in front of Big Ben and put it on the head of the statue of Winston Churchill. Later, the demo turned into a riot, and photos of Winston with a grass Mohican were on the cover of every single British newspaper the next day. It was the most amazing bit of vandalism, because it was the perfect logo for this eco-punk movement that was trying to reclaim the streets, bring an end to global capitalism, and defend the right to sit in a park all day getting wasted on discount lager.

Your art is still free on the streets but costly in the galleries. What dictates that?

What I find is I don’t have much say in what things cost. Every time I sell things at a discount rate, most people put them on eBay and make more money than I charged them in the first place. The novelty with that soon wears off.

You were talking about how you want your books to be cheap because they show the work in the context of the street, as well as the installations in museums and other pranks, which are actually honest representations of your work. But then people want objects, so they’re going to want the canvases and things like that, and you’re just kind of accepting that people fetishize objects and are willing to pay a lot for the status of owning something that they can hang up.

I stenciled the door of an electrical block in south London and recently someone sawed it off and sold it at a famous auction house for £24,000, but in that same week Islington council power sprayed off eight of my new stencils on one road. What I’m finding is art is worth whatever someone is willing to pay for it, or willing to pay to not have to look at it.

The redistribution of the wealth then allows you to have that freedom to put work on the street without the pressure of having to sell a thousand cheap canvases – work that’s free and accessible. It really means that the art objects, the canvases, only really play into the people that think in an elitist way and have the money. So really, it kind of balances out. That’s an issue that a lot of artists have. They believe that their work should be accessible to a lot of people, and that actually is the opposite of the way the art world works.

The art world is the biggest joke going. It’s a rest home for the overprivileged, the pretentious, and the weak. And modern art is a disgrace – never have so many people used so much stuff and taken so long to say so little. Still, the plus side is it’s probably the easiest business in the world to walk into with no talent and make a few bucks.

The murals you did in Palestine, I would assume, involved personal risk. You’re there, and you could definitely get some people pissed off and put yourself in jeopardy.

Every graffiti writer should go there. They’re building the biggest wall in the world. I painted on the Palestinian side, and a lot of them weren’t sure about what I was doing. They didn’t understand why I wasn’t just writing “down with Israel” in big letters and painting pictures of the Israeli prime minister hanging from a rope. And maybe they had a point. The guy that I stayed with got five days with the “dirty bag” for waving a Palestinian flag out a window. The dirty bag is when Israeli security services get a sack, wipe their shit on it, and put the bag over your head while your hands are tied behind your back. I spat out my falafel as he was explaining that to me, but he just goes, “That’s nothing. My cousin got it for two weeks without a break.” It’s difficult to come home and hear people complaining about reruns on TV after that. It’s very hard for the locals to paint illegally over there. We certainly weren’t doing it under the cloak of darkness; you’d get shot. We were out in the middle of the day, making it very clear we were tourists. Twice, we had serious trouble with the army, but one time the Palestinian border patrol pulled up in an armored truck. The Israeli government makes a big fuss about how they own the wall, despite building it right through the farmland of Palestinians who have been there for generations, so the Palestinian border police don’t give a shit if you paint it or not. They parked between the road and us, gave us water, and just watched. It’s probably the only time I’m ever going to paint whilst being covered by a cop from a roof-mounted submachine gun.

Did they realize that it favored the Palestinian perspective?

I have sympathy for both sides in that conflict, and I did receive quite a bit of support from regular Israelis, but if the Israeli government had known we were going over there to do a sustained painting attack on their wall, there’s no way that we’d have been tolerated. They’re very paranoid. They don’t want the wall to be an issue in the West. On the Israeli side of the wall they bank it up with soil and plant flowers so you don’t even know its there. On the Palestinian side it’s just a fucking huge mass of concrete.

You’ve never really been busted to the point of potentially not being able to do street art, but that’s always a possibility. I could be wrong – you could be incredible and never get caught, but everybody gets caught at some point. What would you do if you were put in that position? Would you rent walls? Would you try to find legal walls? Would you still try to find ways to have work on the street and still maintain your anonymity to a degree, but keep it out there through more legal means? Would you move to another country? What would you do?

I’m always trying to move on. You’re not supposed to get dumber as you get older. You’re not supposed to just do the same old thing. You’re supposed to find a new way through and carry on. I invest back into the street bombing from selling shit. Recently, I’ve been pretending to be a construction manager and paying cash to get scaffolding put up against buildings, then I cover the scaffolding with plastic sheeting and stand behind it making large paintings in the middle of the city. I could never have done that a few years ago. Plus, I’m always interested in finding new places to hit up; it’s easier to break into zoos and museums than train lay-ups, because they haven’t had so much of a graffiti problem in the past. Ultimately, I just want to make the right piece at the right time in the right place. Anything that stands in the way of achieving that piece is the enemy, whether it’s your mum, the cops, someone telling you that you sold out, or someone saying, “Let’s just stay in tonight and get pizza.”

Banksy will be showing some of his work in Los Angeles from September 15-18, 2006. For exact location and other details, check out http://www.banksy.co.uk

Exit Through the Gift Shop interview with AJ Schnack.

All These Wonderful Things, by AJ Schnack . As seen on http://www.banksy.co.uk 10 January 2011

December 21, 2010

Banksy (Yes, Banksy) on Thierry, EXIT Skepticism & Documentary Filmmaking as Punk

Note – The second in a series of interviews with the directors of some of our favorite nonfiction features of 2010…

Whenever the subject of EXIT THROUGH THE GIFT SHOP has come up in casual or not-so-casual conversation over the past year, a vigorous discussion has followed. I’ve seen master filmmakers, newcomers, film critics and non-pros all engage in excited, lengthy dissections of the film – sometimes about what’s real, what they suspect is not – often about the film’s profound take on art and commerce. In the end, no matter what point of view the individual holds, the conclusion seems to always be that it’s a major work in the nonfiction canon.

One would be forgiven for not expecting all this when Sundance announced EXIT as a late addition to the 2010 festival. The debut film by Banksy – the anonymous British artist who gained notoriety and fame for his often-politically charged work that would turn up in some very unusual places (inside museum galleries, on the West Bank wall that separates Israelis and Palestinians) – EXIT would leave the festival spurring numerous distribution offers and go out on its own, working with sales agent John Sloss and distributor Richard Abramowitz to bring the film to theatres in the spring. And after a somewhat surprising (relief was more like it) inclusion on the Academy’s Documentary Feature shortlist, the film finds itself smack in the middle of Best-of-the-Year conversations. It’s nominated for the Documentary prize at the Film Independent Spirit Awards and it’s up for 6 awards at next months Cinema Eye Honors, including Outstanding Feature and Outstanding Debut, not to mention the numerous film critics prizes its been garnering (yesterday, it was announced as the Best Documentary and Best First Feature on indieWIRE’s annual critics poll).

Over the past month, we’ve had the opportunity to spend some time with the team behind EXIT – producer Jaimie D’Cruz and editor Chris King – including hosting the duo at a screening here in Los Angeles at Cinefamily earlier this month. In their presence, I witnessed numerous others trying to find out what Banksy thinks of this or that.

I had my own questions and Banksy and team were kind enough to get me his answers (via email, of course)…

All these wonderful things: One thing I’ve heard repeatedly from members of your team was that, early on, you were alone in your conviction that Thierry could and should be the narrative focus of the film – long before his show in LA that concludes the movie. What drew you to Thierry as a film character and, aside from the fact that he had a lot of archival material about street art at his fingertips, why did you think that he could sustain the film’s narrative arc?

Banksy: Thierry’s entertainment potential wasn’t difficult to spot – he actually walks into doors and falls down stairs. It was like hanging out with Groucho Marx but with funnier facial hair. Thierry arrived at a point when my world was becoming infested with hipsters and heavy irony, so his exuberant man-child innocence was fun to be around. Maybe I convinced myself Thierry was a good subject just because I liked him. I’d be lying if I told you the first time I met him I thought ‘this man’s life will deliver a good narrative arc’.

From the outset there are problems with any movie about graffiti because all the good artists refuse to show their face on camera. I needed the film to be fronted by a personality the audience could engage with. The producer Robert Evans said that ‘vulnerability’ is the most important quality in a movie star and that’s a hard thing to portray if all your interviewees have masks over their faces.

ATWT: It’s clear in the film that you rely on a team of people to create your artwork. What, if anything, was different about the filmmaking process, and the work you did with that team – Jaimie and Chris and others? And how did you know when you’d found the right collaborators?

B: I paint my own pictures but I get a lot of help building stuff and installing it. I have a great little team, but I tell you what – they all hate this fucking film. They don’t care if its effective, they feel very strongly that Mr Brainwash is undeserving of all the attention. Most street artists feel the same. This film has made me extremely unpopular in my community.

ATWT: When I saw the film, it didn’t strike me as anything but a true documentary. Perhaps because I live in Los Angeles and I’ve seen MBW’s art in my neighborhood and remember his big show, but also because it’s clear that the scene where Thierry meets Shepard Fairey is at least nine years old (there’s now a big movie theater complex across the street that doesn’t exist in the footage that Thierry shot). Yet, particularly when the film was opening last spring, there seemed to be this undercurrent of suspicion, perhaps because of the press’ desire to paint you as a prankster, that the film was trying to pull one over on us. How much of that conversation have you been paying attention to and what was your take on it?

B: Obviously the story is bizarre, that’s why I made a film about it, but I’m still shocked by the level of skepticism. I guess I have to accept that people think I’m full of shit. But I’m not clever enough to have invented Mr. Brainwash, even the most casual on-line research confirms that.

Ordinarily I wouldn’t mind if people believe me or not, but the film’s power comes from the fact it’s all 100% true. This is from the frontline, this is watching an art form self-combust in front of you. Told by the people involved. In real time. This is a very real film about what it means to ‘keep it real’.

Besides, if the movie was a carefully scripted prank you can be sure I would’ve given myself some better lines. I would’ve meticulously planned my spontaneous off-the-cuff remarks. I love that famous Jack Benny come-back to a heckler – “You wouldn’t say that if my writers were here.” But I’ve always wondered – did his writers tell him to say that?

ATWT: One of the more electrifying and sometimes terrifying moments for any filmmaker is seeing their work with an audience for the first time. Have you seen EXIT with an audience and, if so, what was that experience like?

B: Unfortunately I haven’t seen it with an audience. The nearest I got was going to the cinema to see ‘Precious’. They played my trailer beforehand and someone two rows in front shouted ‘OH MY GOD, BANKSY IS SUCH A SELL-OUT’ and I shrank into my seat.

ATWT: What do you think that you discovered about the form of documentary while making this movie and is there any correlation to your other artistic work? Were you a fan of documentary prior to making the film and, if so, what were some of your favorite films? Did any of them influence what you did on EXIT?

B: I’m from a generation for whom documentary isn’t a dirty word. It doesn’t have to mean endless shots of penguins set to classical music. Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock seemed completely punk to me. And the most punk thing of all was they brought their story undiluted to the multiplex.

Documentaries have an important role in recording culture that’s unlikely to make it into the history books. DOGTOWN AND Z-BOYS was the Bill of Rights for skate culture. Having said that, my film was never going to be an authoritative history of street art. Or even an authoritative history of the selling-out of street art. We realized halfway through the edit that the ending needed to be as unresolved as possible. I’ve learnt from experience that a painting isn’t finished when you put down your brush – that’s when it starts. The public reaction is what supplies meaning and value. Art comes alive in the arguments you have about it. If we’ve done our job properly with EXIT, then the best part of the entire movie is the conversation in the car park afterwards.

ATWT: Do you think that there are specific challenges for you and your team due to your anonymity? Did that ever make the process easier or more difficult in a way that other documentary filmmakers may not suspect?

B: Deciding who to work with is a balancing act between people’s abilities, and their ability to keep their mouth shut. We’ve had some pretty sensitive footage of different artists go through our hands. Thankfully it’s all been burnt now.

My inability to go around schmoozing people might have hurt the film on one level, but on another level I’m a volatile drunk and it’s probably been an enormous blessing.

ATWT: The Toronto Film Critics recently named EXIT as the Best First Feature of 2010, which begs the question of whether there will be another film in the future – and, particularly for my own curiosity, would it be another documentary? If so, would you seek out a subject or would you wait for something to cross your path that ignited your desire to create a film about it?

B: The art I make is similar to film – my paintings are essentially freeze frames from movies that are playing in my head. I think its pretty clear that film is the pre-eminent art form of our age. If Michaelangelo or Leonardo Da Vinci were alive today they’d be making Avatar, not painting a chapel. Film is incredibly democratic and accessible, it’s probably the best option if you actually want to change the world, not just re-decorate it.

Posted by AJ Schnack on December 21, 2010

TrackBack

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://www.typepad.com/services/trackback/6a00d8341bff3653ef0148c6f192f8970c

Banksy goes to Bethlehem

Financial Times. 15 December 2017

By Jan Dalley

https://www.ft.com/content/b1e914a2-df94-11e7-a8a4-0a1e63a52f9c

Bethlehem, December 2017. Rockets are screaming up into the night sky, exploding with ear-splitting bangs, again and again. The sounds of a battleground. But on the night of December 2, these are only fireworks and the occasion is the annual lighting-up of the giant Christmas tree in Bethlehem’s Manger Square. A huge crowd of people cluster around, their upturned faces caught in the flickering light of thousands of smartphones held high, chanting a countdown as a light show streaks across the tree, before a canopy of bulbs overhead, and the whole tree itself, flash into gaudy colours and the firework show begins. All to the thumping beat of Arab pop. It’s an event that might have sent the original ox and ass running for the hills: more Atlantic City than “O Little Town”. Across the square, however, in a small arched doorway, another Christmas message has appeared — silently and unnoticed, in the past day or so. Painted on the door in cursive English script, it reads: “Peace on Earth”. There follows an asterisk, in the shape of a Bible-storybook star, and underneath, in much smaller letters: “Terms and conditions apply”. Just a few days later, the unrest following US president Donald Trump’s official recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital would vividly illustrate those terms and conditions, and this salutation, from the British graffiti artist Banksy, would take on a new irony.

Banksy’s unseen presence in this part of the West Bank has become increasingly powerful. Interviewed over email (the only way to communicate with the famously anonymous artist), he says jokily that when he first came to the region, “I was mainly attracted by the wall: the surface looked like it would take paint very well.” The wall in question is, of course, the impenetrable 30ft concrete-and-wire barrier, with its guarded watchtowers, that runs alongside and through the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem. It carves through Bethlehem in a strange double-U shape, to ensure that the holy site of Rachel’s Tomb remains on the Israeli side. This serpentine course means that there is an awful lot of wall in Bethlehem, and alongside the Aida refugee camp on its outskirts (home to more than 5,000 Palestinians); and the wall does indeed take paint well. The full length is a riot of graffiti, by a mass of different hands, painted and overpainted again and again — many recent ones are giant cartoons of Trump, including one in which he is hugging and kissing a watchtower. Banksy has been working here on and off since his first visit in 2003. By that time he was already well known in Britain as a clandestine street artist, first in his native Bristol, then in London and elsewhere. But his move into the commercial big time was yet to come. Techniques for illicitly removing his work from walls were rapidly being perfected, while Banksy’s then gallerist, Steve Lazarides, was a keen legal marketer. When in 2007 Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie forked out a cool £1m for a Banksy work, other celebrities — among them Christina Aguilera, Damien Hirst and Kate Moss — followed suit. Justin Bieber had Banksy’s famous image of the little girl with a balloon tattooed on his forearm. As Lazarides put it at the time, buyers in this Banksy craze were “rag trade, City boys or celebrities, [usually] under 45”. In 2008, “Keep It Spotless (Defaced Hirst)” fetched $1.87m at Sotheby’s; it remains the artist’s auction record. Since then, various houses, shops and even sheds that host Banksy works have come to the market for several times their actual property value. No one knows, though, the prices of the illicit sales of work stolen from walls.

Despite (or perhaps because of) his market success, Banksy gathered his share of detractors. He was accused of copying ideas, especially from French street artist Blek le Rat, and often regarded as a prankster whose hit-and-run visual aphorisms were amusing rather than deep. Yet all the commercial activity and sales of merchandise and new work via Pest Control, the company he set up in 2009 largely to control the flood of fakes, mean that Banksy’s personal wealth is conservatively estimated at some £20m.

Despite the artist’s best efforts, the faking, thieving and destruction of his works continues everywhere in the world. In Bethlehem, too, powerful images have often disappeared surreptitiously, sometimes almost as soon as they have appeared on surfaces around the town or on the wall itself. One 2007 painting that raised hackles locally, of a donkey having its identity papers checked by a heavily armed Israeli soldier, has vanished and is — according to Banksy’s agent Jo Brooks — currently for sale on the international market. What’s more, cowboy gift shops, unashamedly selling Banksy knock-offs and copies, are everywhere. There is even a large one, bearing its slogan “Make hummus, not war”, right up against the wall of Banksy’s hotel. The Walled Off hotel (pronounced Waldorf) was opened earlier this year, aimed mainly at international visitors, with a range of rooms from the luxurious to a no-frills bunk-bed option at $60 a night. Starting with the over-lifesized plaster chimpanzee dressed as a 1930s bellboy at the front door, the period luggage he is carrying spilling ladies’ undies, the place is packed with Banksy-ish visual jokes, as well as his artwork. It proudly claims to be the hotel “with the worst view in the world” because it stands barely five metres from the looming expanse of the barrier, which at this point runs along what used to be a bustling shopping street, now a semi-deserted, rubble-strewn, potholed lane.

Graffiti rules here: this must be the only hotel where the guest information sheet includes advice about where to buy paint and hire ladders. From its pleasant terrace, the colourfully graffitied concrete in front of you seems almost jaunty in the bright daylight. At night, though, the wall’s full sinister menace is inescapable. Banksy is not new to ambitious enterprises: two years ago he set up Dismaland, a temporary “bemusement park” in Weston-super-Mare. Offering a dark twist on Disneyfied family entertainment, it was a place, as its publicity said, “where you can escape from mindless escapism”. Two years before that he announced a “residency” in New York, with plans to create a work somewhere around Manhattan and Brooklyn on each day of his 31-day stay. One of his stunts was to set up a stall beside Central Park, selling authentic signed pieces for $60 each. Only three were sold.

But a hotel? In such a location? Given Banksy’s persona, it’s hardly surprising that some people assumed it was a joke. But this time, it seems, the joker was in earnest. “To be completely honest, I knew very little about the Middle East when I first went there. You know — just a sense from the news that it was a bunch of people habitually killing each other,” he says. “On my first trip to Palestine I arrived at night and was driven straight behind the wall. So I assumed the poverty, the donkeys, the water shortages, the electricity blackouts were all just facts of life in that part of the world. I was completely astounded when a week later I left through the checkpoint into Israel and 500 yards down the road there were expensively paved shopping centres, roundabouts planted with palm trees, brand new SUVs everywhere. Seeing the disparity between the two sides was shocking, because you could see the inequality was entirely avoidable.”

Over time, though, his involvement with the region has deepened from visiting graffiti artist to investor. The main reason he bought an old pottery works and converted it into a hotel, he says, “was for Wisam, my fixer”. This is Wisam Salsaa, now manager of The Walled Off, and the artist’s local representative — in everything, it seems, since keeping yourself entirely secret requires devoted allies. “I’d become good friends with [Wisam],” Banksy continues. “But the occupation was making him so fed up he was on the verge of leaving Palestine for a job washing dishes at a Belgo’s in Rotterdam. This is a man who runs several businesses, speaks five languages, employed half a dozen people, who was intelligent, brave and funny. I thought — it’s vital people like him don’t leave.” And then, in the inevitable twist, he adds, “Plus I didn’t want him coming to sleep on my couch.”

On the morning after Bethlehem’s tree-lighting party, the acclaimed film director Danny Boyle is standing in the middle of the dusty car park adjoining the hotel. Salsaa is there, organising everything as always, and so is Riham Isaac, Boyle’s Palestinian co-director in this newest Banksy project. There’s a scaffolding stage with a lighting rig, a few rows of plastic chairs, a huge camera boom, a couple of bickering sheep and an elegant white donkey tied up in the shade. It doesn’t look like a place where, in just a few hours, they will produce The Alternativity, a Christmas play performed by local children. This morning, too, high on the wall overlooking the car park, a new Banksy piece, in his signature stencilled style, has appeared. It shows two winged cherubs, one holding a crowbar, tugging furiously at a gap between the concrete slabs of the wall, trying to jimmy it open.

Will The Alternativity hold a similarly political message? Apparently not. “I just got an email from Banksy out of the blue,” says Boyle. “I’d never been in touch with him before, though I knew his work of course. I respected what he was doing. And he just asked me to do this, and I said yes.” Boyle was paid £1; the contract describes him as “presenter”. On an earlier visit, Boyle had recruited Isaac, a local theatre director and teacher, to work on the project. She explains that she found and auditioned the children to perform and sing through Facebook. Many of the locals involved are Christian, though there are one or two hijabs under the Santa hats worn by the choir.

A film of the whole project is under way, directed by Jaimie D’Cruz, who worked with Banksy on his 2010 documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop. D’Cruz tells me that, even for Boyle, it was hard to hire equipment here. And although it is happening only a few hundred yards from the nearest checkpoint, three Israeli photographers declined to take pictures for the FT. Yet it feels peaceful, almost sleepy. Dusk falls quickly in the winter afternoons here, and when several hot dusty hours have passed, during which the two children’s choirs, the dancers and performers, even the donkey, have rehearsed the play, the five o’clock start is in darkness. Strapping security guards in military boots, their bulletproof vests with the strangely cosy slogan “PalSafe” on their backs, stride around as the lights start to glitter and the transformation of the dingy car park is complete. The hideous wall looming just behind us is forgotten.

People arrive, dressed up and excited — families with noisy young children eating ice cream, older people, some local dignitaries who get the few chairs while everyone else mills around. There’s a small number of foreigners. Then it begins: carols and songs, sweetly sung in Arabic and a little English; some slapstick; some dancing; Mary on that donkey, of course; three comic and strident “wise women” instead of the kings; and the Christmas story is told. Despite the magic wand of an internationally famous director and some very expensive touches (a noisy snow machine, for instance), it was a Christmas play like thousands the world over: strangely reassuring, absurdly touching. The involvement of many dozens of local children and families in The Alternativity was a tribute to weeks of work on Isaac’s part. Banksy reveals a different aspect of the project: “The nativity was conceived as a rather clumsy Christmas stunt,” he says. “But almost as soon as the film crew arrived they reported back saying, ‘We’re going to have to reflect the local unease with the hotel,’ to which I said — unease? It turns out a lot of locals are rather suspicious of the project. In the end the Nativity play was wildly popular and has engaged with lots of children and their families. So the Nativity discovered a problem and then solved it — Merry Christmas.”